The Ottawa Citizen from Ottawa, Ontario, Canada • 138

- Publication:

- The Ottawa Citizeni

- Location:

- Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

- Issue Date:

- Page:

- 138

Extracted Article Text (OCR)

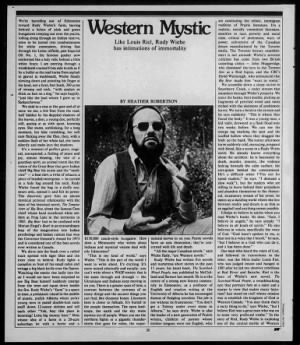

Western Mystic Like Louis Riel, Rudy Wiebe has intimations of immortality BY HEATHER ROBERTSON "SSSi' 7 -Ail vrvv" 7 are continuing the ethnic, immigrant tradition of Prairie literature. It's a realistic, socially committed literature, sensitive to race, poverty and social class, critical of pretension, wary of power, subversive of the Canadian dream manufactured by the Toronto media. The Toronto literary establishment is not amused: Wiebe's severest criticism has come from two British carpetbag critics John Muggeridge, who dismissed the hero in the Toronto Star as a Red hippie, and the CBC's David Watmough. who announced that Big Bear made him "want to vomit." We scramble down a steep ravine 10 Strawberry Creek, a rocky stream that meanders through Wiebe's property. We scour the banks, bent double, picking up fragments of petrified wood and rocks etched with the skeletons of prehistoric leaves.

We turn a bend in the stream and he says suddenly: "This is where they found the body." It was a young man, a kid really, drowned in a flash flood only two weeks before. We can see the orange tag marking the spot and the scuffed hollow where they dragged the body up the bank. The sunny afternoon turns suddenly cold, menacing, pregnant with blood, like a scene in a Rudy Wiebe novel. He already knows everything about the accident: he is fascinated by death, murder, insanity, the violence lurking beneath the calm surface, the corruption behind the conventional. He's a difficult writer not for speed readers," he says.

"I demand a slow but for readers who are willing to leave behind their prejudices and abandon themselves to the rhetorical, incantatory stream of his prose, he opens up a dazzling world where the line between reality and dream is as thin as an eggshell and anything seems possible. It helps to believe in spirits when you read Wiebe's books. He does. "Sure, I believe in angels," he says simply. "I believe in all kinds of spirits." He also believes in voices, specifically the voice of God.

"God hasn't spoken to me, at least not in a voice that I heard," he says, "but I believe in a God who can do it, and it has been done." One man who heard the voice of God, and followed its instructions to the letter, was the Metis leader Louis Riel, who was judged insane and hanged in 1885 after he led two abortive rebellions at Red River and Batoche. Riel is the hero of Wiebe's new novel. The Scorched-Wood People, a swashbuckling epic that portrays him as a saint and a martyr (a view that makes many historians' hair stand on end) whose mission was to establish the kingdom of God in Western Canada. "You may think that's a nutty thing to do," says Wiebe, "but I believe Riel was a great man who was on to some very profound truths." In the story of Riel, Rudy Wiebe is exploring one of the central myths of Western We're barrelling out of Edmonton toward Rudy Wiebe's farm, leaving behind a lichen of pink and green bungalows creeping out over the prairie, rolling along through an Indian reserve, soon to be turned into condominiums for white commuters, driving fast through the Leduc oilfield, past Imperial Oil No. 1, the famous gusher now enshrined like a holy relic behind a little white fence.

I am peering through a windshield cracked from side to side as if by a bullet as the road turns from asphalt to gravel to washboard, Wiebe finally slowing down and pointing his finger at his land, not a farm, but bush, 360 acres of swamp and rock, "with poplars as thick as hair on a dog," he says happily, "just like the land where I grew up in Saskatchewan." We skid to a stop at the gate and all at once we see, a few feet from the road, half hidden by the dappled shadows of the leaves, a deer, a young doe, perfectly still, gazing at us with quiet, knowing eyes. She stares, unblinking, for a long moment, her hide trembling, her soft ears flicking away the flies, then, with a sudden flash of her white tail, she turns silently and melts into the shadows. It's a moment of perfect grace, magical, unexpected, a feeling of peace and joy, almost blessing, the visit of a guardian spirit, an animal totem like the vision of the Great Bear that gave Indian chief Big Bear his name and the "medicine" a bear claw, a twist of tobacco, a piece of braided sweetgrass he carried in a hide bag around his neck. Rudy Wiebe found the bag in a stuffy museum attic, opened it and felt its power. The discovery gave him an almost mystical personal relationship with the hero of his historical novel, The Temptations of Big Bear, about the famous Cree chief whose band murdered white settlers at Frog Lake in the territories in 1 885.

Big Bear (not to be confused with Marian Engel's Bear) is an extraordinary leap of the imagination into Indian psychology and Indian culture that won the Governor General's Award for 1973 and is considered one of the best novels ever written in Canada. We drive into the bush over a rutted track spotted with tiger lilies and the trees close in behind. Rudy lights a campfire in front of his small cabin and swings a big black kettle over the flames. Watching the smoke rise lazily into the air I would not have been surprised to see Big Bear himself suddenly emerge from the trees and squat down beside the fire. Rudy Wiebe's "farm" is a space in time, a prehistoric island in the middle of plastic, prefab Alberta where porky young men in pastel double-knit suits stufT down 12-ounce sirloins and tell each other "Yah, boy this place is booming! Lotta big money here." Men whose idea of a farm is a 20-acre suburban lot with a horse and a natural moves in on you.

Prairie novels have an epic dimension; they're concerned with life and death. "AH the major Canadian novels," says Wiebe flatly, "are Western novels." Rudy Wiebe has written five novels and numerous short stories in the past 15 years; his latest book. The Scorched-Wood People, was published by McClelland and Stewart last month. He is at the centre of a strong new literary community in Edmonton; as a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Alberta he has encouraged dozens of fledgling novelists. The job is not without its frustrations: "You don't get a Tolstoy under every stone in Alberta." he says dryly.

Wiebe is also the leader of a new generation of Prairie writers, children of parents whose mother tongues were not English, who $150,000 ranch-style bungalow. How does a Mennonite who writes about Indians and mystical visions deal with oily Edmonton? "This is my kind of world, says Wiebe. "This is the part of the world I want to write about It's exciting. It's more mixed ethnically and racially; you can't write about a WASP society that is the same through and through the Ukrainians and Indians keep moving in on you. There is a greater span of time, a contrast between the newness of so many things and the ancient things you can find, like dinosaur bones.

Literature here is closer to folktale. It's buried in the people themselves. The open landscape, the earth and the sky make mystics out of people. When you see the northern lights or a gigantic thunderstorm that goes for miles, the super.

Get access to Newspapers.com

- The largest online newspaper archive

- 300+ newspapers from the 1700's - 2000's

- Millions of additional pages added every month

Publisher Extra® Newspapers

- Exclusive licensed content from premium publishers like the The Ottawa Citizen

- Archives through last month

- Continually updated

About The Ottawa Citizen Archive

- Pages Available:

- 2,113,492

- Years Available:

- 1898-2024