The Los Angeles Times from Los Angeles, California • 69

- Publication:

- The Los Angeles Timesi

- Location:

- Los Angeles, California

- Issue Date:

- Page:

- 69

Extracted Article Text (OCR)

Cos Anflcles Simes Friday, May 15, 1981 Part 23 Mexican-American Stayed in World War II Camp Volunteer Internee Recalls Japanese-American Relocation Center went along for the ride," he wants people to remember that it happened and that people suffered, physically, financially and psychologically. "To most people," he says, "when the camps were gone, they were gone." resent the Manzanar YMCA at a Hi-Y conference in Estes Park, Colo. It was on the trip, he remembers, that he and his Japanese friends were refused service at a Chinese restaurant in Colorado. In Spanish, Manzanar means "apple orchard," but it was a barren desertland in the Owens Valley, its water long since diverted to Los Angeles, to which the evacuees were moved in the spring of 1942, soon after President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066.

William Hohri, now a computer programmer in Chicago, was a classmate of Lazo at Manzanar. "He was one of the most popular people in camp," he recalls. "Everyone got along with him." Hohri, who was from North Hollywood, met Lazo at camp and they quickly became friends. Says Hohri, "He fit in so well, so comfortably. He didn't make a big deal out of it" Today, Hohri is spearheading the efforts of the Chicago-based National Council for Japanese-American Redress, which has raised $27,000 toward initiation of its lawsuit seeking redress for those who were interned.

"It's practically impossible to get anything passed through legislation," says Hohri. "We think the way to go is through the courts." They would leave it to the courts to decide the amount of financial remuneration for each individual, Lazo supports the council's efforts. community churches, giving instructions for evacuation. "That's when it really hit home." Until then, fact had been laced with rumor. "We would hear that so-and-so's dad was picked up by the police.

Some kids didn't even attend school because they were afraid to go out Sometimes we'd go to the store and bring these people groceries." The Army Corps of Engineers built 10 camps in the seven Western states; at their peak they housed 120,000 evacuees, of whom 70,000 were U.S. citizens. Almost all of the 120,000 were longtime residents of the United States and some had relatives serving in the U.S. Armed Forces. Lazo remembers, "There were some Niseis (second generation) who'd never before been with so many Japanese.

Some of them felt more comfortable with me, even though I was more Japanese than many of the others." Chuman concludes that the Japanese on the West Coast were "victims of hysteria, misunderstanding and a long-standing racial hatred." Cries for internment came from the American Legion, the California Farm Bureau, from some labor unions. Syndicated columnist Henry McLemore of the San Francisco Examiner wrote: "Herd 'em up, pack 'em off and give 'em the inside room in the badlands. Let us have no patience with the enemy or with anyone whose veins carry his blood. Columnist Westbrook Pegler agreed. "To hell with habeas corpus," he wrote.

The Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce endorsed mass evacuation; Earl Warren, then attorney general of California, warned that disaster was inevitable if the Japanese were not incarcerated. "It never should have happened," says Lazo. "There was no reason for it. These people weren't a threat. And they didn't need to be protected." By the luck of the draw, Lazo went to Manzanar but most of the friends he had signed up to be with were assigned to the Heart Mountain, relocation camp.

Soon Lazo, the hustler, had a camp job, delivering mail for $12 a month. Later, he was a $16-a-month recreation director. He was also class president, a so-so student of 150, 1 was ranked 150. 1 didn't mind being 150 in that and, frequently, he was the "go-between" in his classmates' romances. "I had the confidence of their parents," he explains.

The class of '44 danced to the music of their own band, the Jive Bombers. They drank gallons of Hawaiian punch and ate stacks of deviled egg sandwiches. They brought trees from the foothills to plant inside the compound. It was a busy time. "We didn't just sit around and complain," says Lazo.

In the summer, the heat was unbearable; in the winter, the sparsely rationed oil didn't adequately heat the tarpaper-covered pine barracks with the knotholes in the floor. The wind would blow so hard it would toss rocks around. But, Lazo remembers, when everything looked grim, Toyo Miyatake, who saw the world of Manzanar through the lens of his contraband handmade camera, "would always point out the beauty around us." (In 1978, "Two Views of Manzanar," the photos of Miyatake and of Ansel Adams, was an exhibit at UCLA. Lazo left the camp only twice, once to appear before his draft board in Lone Pine for induction, once to rep In August, 1944, Ralph Lazo left Manzanar to join the Army. He trained at Camp Roberts, then shipped out of Monterey to the South Pacific during the campaign for liberation of the Philippines.

In August, 1946, Staff Sgt. Ralph Lazo, U.S.A., was ordered to military police duty in Japan. He remembers, "All my boys were Southern boys. I'd tell them I was from the South, too." It worked. He didn't get to serve in the all Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the much-decorated unit that fought in the European Theater and captured his imagination when he was a kid at Manzanar.

"They set the example for us," he remembers. "Imagine fighting miles away while your mothers, fathers and brothers are interned." After the war he enrolled at UCLA where, together with the handful of other Hispanic students, he aided voter registration drives in East Los Angeles and worked with gang kids in the barrio. In three years, he graduated with a sociology degree and went to Chihuahua, Mexico, to help establish a technical institute. He stayed almost four years and married a Mexican woman (they are divorced and have three children). Back in Los Angeles, he was a social worker in the Japanese-American community, working with the Sansei generation, and in 1955 began as a teacher and counselor with the city schools, where he stayed until coming to Valley College in 1970.

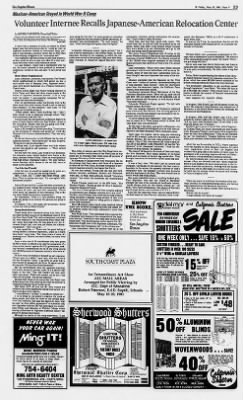

By BEVERLY BEYETTE, Times Staff Writer America's only non-Japanese evacuee. Ralph Last. 18, of Los Angeles will leave Manzanar Relocation Center soon to join the United Suits Army. News release fraai DeserloMM the laterler. War Relecaliea Aalherir, If there was a moment of truth, an instant in which Ralph Lazo had determined that he would go with his Japanese-American friends to internment camp, perhaps it was during a wartime winter day in 1942 when he was helping a neighbor at an "evacuation sale." The neighbors had been forced to sell their property, as they would be able to take only what fit in their suitcases when they went to the relocation center.

As Lazo helped a buyer load a lawnmower into his car, the buyer, pleased to have profited by someone's misfortune, turned to him and said, "I sure jewed that Jap!" Multi-Ethnic Neighborhood Lazo, a Mexican-American, was stunned. The Temple Street neighborhood in which he'd grown up was a multi-ethnic mix of Basques, Jews, Japanese-Americans. He'd played basketball on a Filipino Community Church team. Central Junior High was within walking distance to Little Tokyo and Lazo had often shared meals at the homes of Japanese-American friends. "I fit in very well," he recalls.

"I was peaceful, easygoing. We developed this beautiful friendship." Now, by government order, his friends were to be taken away from their homes, forced to sell or abandon their property. "It was immoral," says Lazo, "it was wrong, and I couldn't accept it. "These people hadn't done anything that I hadn't done, except to go to Japanese language school. They were Americans, just like I am." One day Lazo was having lunch at Belmont High with some of these friends when one, Isao Kudow, turned to him and asked, "Ralph, what are you going to do without us? Why don't you come along?" Lazo, at 16, needed no further prodding.

"I went down to the old Santa Fe Station and signed on" (with the Wartime Civil Control Administration). That was early in 1942. He did not have to lie, to tell officials that he was of Japanese ancestry. "They didn't ask," he says. He grins.

"Being brown has its advantages." Looking back, Lazo figures there was little chance anyone was going to ask questions "They wanted these people in." For the next two years, Lazo would live at Manzanar, the relocation camp behind barbed wire fences in the dusty, desolate Owens Valley. There he would graduate from high school (Manzanar class of '44), play football, emcee Saturday night dances in the rec hall, learn to speak a little Japanese. 'Just Like Jap Friends' After the war, he would be singled out by some as a sympathizer "a Jap, just like his Jap friends." Sure, it hurt. But "I knew right from wrong," says Lazo. Then he smiles and says, "I'm one-eighth Irish.

Sometimes it shows. Lazo is 55 now and for 11 years has been a counselor at Los Angeles Valley College. He is reticent about what he did almost 40 years ago and asks repeatedly, "Please write about the injustice of the evacuation. This is the real issue. Ralph Lazo is just a consequence." He emphasizes, "This is a very personal thing.

No books are going to be written. No pictures are going to be made." He repeats, "I'm a very quiet, private person. I blend in real well with my Nisei friends." Strong Bonds Remain Those bonds have remained strong. Last June, Lazo attended the 36th reunion of the Manzanar class of '44 at the New Otani Hotel. The table centerpieces, auctioned off, were replicas of the watchtowers from which military police had kept their 24-hour guard over the internees.

Ralph Lazo, one-time yell leader, led a Manzanar spellout "Give mean M. It was a good day "There was this great feeling of having shared a common experience, unjust as it might have been," says Lazo. "But those years of camp, it's showing on us. There's too much illness, too many of us divorced." Lazo is also one of 10 contributors who have given $1,000 or more to a fund to be used for preparation of a class-action lawsuit against the U.S. government, seeking financial compensation for all of the living among the 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry who were interned.

In little ways, he thinks of himself as part Japanese. "Every once in a while," says Lazo, who now lives in the San Fernando Valley, "I go down to Little Tokyo, treat myself by going into the Kyoto Drugstore and ordering sushi. It brings back fond memories." But his involvement with the Japanese-American community has been private, quiet. It is a pattern that began in the '50s. "The '50s weren't the most open time," says Lazo.

"I had to be careful, not for me-I can take care of myself but for my children." Beyond that, there is his conviction that Ralph Lazo did nothing more than stand up for what he believed in, the least he expects of any human being. The heros, he'll tell you, are the men, women and children who were imprisoned behind that barbed wire, who lived there with dignity. "I was different," he says. "I could have walked out." It is to bring to the public's attention the cause of these people, and what he views as the terrible injustices they suffered, that Lazo has agreed to make what he calls "my first public appearance" as America's only non-Japanese evacuee. He will participate in a conference Friday and Saturday at Whittier College, where leading authorities on Japanese-American history will gather to discuss internment.

Although he insists of the camp experience, "I just LARRY ARMSTRONG Lot Angela Times As a teen-ager, Ralph Lazo, 55, was the only non-Japanese in internment camp. That order, in essence, gave the War Department authority to define certain areas of the West Coast as war zones and to evacuate from these areas all persons of Japanese, German or Italian ancestry. No Germans or Italians were ever evacuated. But on the premise that there was a real threat of a Japanese invasion of the West Coast, the mass evacuation of persons of Japanese ancestry was begun that March. No one was exempt.

Young and old, sick and well, doctors, lawyers, professors, farmers and fishermen were sent to what were officially termed "relocation centers," but which the internees call concentration camps. Frank Chuman points out in his 1976 book, "The Bamboo People," written as part of UCLA's Japanese-American Research Project: "Not one of these people had been accused, indicted or convicted of any illegal or criminal act in any court." Further, notes Chuman, they were sent to camp without being accorded a hearing, being advised of their civil and Constitutional rights or being given a chance to prove their innocence. They left behind unharvested crops, beached fishing they forfeited mortgages and they lost leases. Total property losses have been estimated at more than $400 million. Says Ralph Lazo, "The individuals who promoted the evacuation were jealous of the competition of the Japanese farmers," resentful of how hard they worked their leased land.

"The discrimination earlier against the Chinese moved right over to the Japanese-Americans. The boat people, the Vietnamese, they're the victims now." Lazo remembers when the posters went up in the There are scars; he attributes the breakup of his marriage partially to misunderstandings about, and lasting repercussions from, the Manzanar experience. But there are no regrets, except there having been a Manzanar. Would Lazo do it again? "I hope nobody ever has to do it again." fsidel rnor and Cdilmk oMm I IzzJ woven woods I ZStiQERSM sa vi Afse nu Know THE SCORE, And much more in The Times' SPORTS section. Every day.

Cos Angeles (Times SDOTTEQS OtAJ COSTOU FINISHED READY TO KA9H SHUTTERS OYER 100 SIZES 2W WIDE or REGULAR LOOYERS 'oOFF SOUTH CQST PLAZA Both the big, bold wide louvers or the traditional smaller louv- if ers are handcrafted of the fin- est sugar pine. 4 lustrous lac- I quer finishes. Finished wide and regular Louver Shutters LOOK AT THESE SAVINGS afR ON FINISHED WIDE LOUVERS. cXk OFF $193 $164 $483411 TV $184 96' $4051344 Ready to finish Wide $290 $246 $664 $564 and Regular Louvers. An Extraordinary Art Show ALL MALL AREAS Arranged for Public Viewing by O.C Dept of Education Robert Peterson, E.d.D.

Schools May 10-20, 1981 WE WILL INSTALL THESE BEAUTIFUL SHUTTERS IN 4 WEEKS OH LESS. 25 OFF BIFOLD LOUVER DOORS REG. $64.00 LOW 48 Sizes to fit door widths 28" to 72" ON TRACK. Choice of full louvers or botton solid panel. Ready to finish clear white sugar pine.

MO mm I ALur.iinur.1 OFF BLINDS Popular 1" Mini -Blinds In scores of colo- specially low priced for Del Mar's 25th Anniversary Sale. Phone today for our LOW estimate. fSHUTTERSl 5 3 FOR WINDOWS, 1 t3 a ROOM DIVIDERS Eg W0VEUW00DS save! Del Mar Woven Woods are the standard by which all other woven woods are measured. See our beautiful, new Woodworks Line -also SALE PRICEDI MING MIRROR FINISH GUARANTEED FOR 3 YEARS Unique process gives your car a deep, beautiful shine which is so easy to keep clean never has to be waxed or polished! Call now for additional Information 754-6404 r.llllG AUTO BEAUTY CENTER 1520 PONDEROSA COSTA MESA (off Harbor between Adams Baker) OPEN Rain or Shin OTHER SERVICES Undercoatlng Rust Proofing Fabric Protection DESIGNED FINISHED INSTALLED Jeruiooii gutter dorp. 3655 W.

McFADOEN Block East of Harbor). SANTA ANA rZzz2 a TOLL 4 a.AAt tyiAX rx-rvMtn PBEI ESTIMATE FREE (714) 839-3360 ES3.

Get access to Newspapers.com

- The largest online newspaper archive

- 300+ newspapers from the 1700's - 2000's

- Millions of additional pages added every month

Publisher Extra® Newspapers

- Exclusive licensed content from premium publishers like the The Los Angeles Times

- Archives through last month

- Continually updated

About The Los Angeles Times Archive

- Pages Available:

- 7,611,941

- Years Available:

- 1881-2024