The Tampa Tribune from Tampa, Florida • 36

- Publication:

- The Tampa Tribunei

- Location:

- Tampa, Florida

- Issue Date:

- Page:

- 36

Extracted Article Text (OCR)

9-B The Tampa Tribune-limes! Sunday, May 6, 1990 07 macher thumbs the radio microphone to tell Lerro the Pure Oil will not be in the Summit Venture's way. He gets ho answer. 1 r-i 1- T5" III rrrrrrn Tampa Bay V0 I Gulf of Mexico A Greyhound bus, on the two-day, whistle-stop No. 1161 run from Chicago to Miami, pulls out of Tallahassee and heads south on U.S. Highway 19.

Almost exactly 200 straight-line miles to the south-southeast, Capt. John Eugene Lerro, 47, is sleeping in one of the 10 beach cottages that make up the pilots' station at Egmont Key at the mouth of Tampa Bay. He has been there since leaving an outbound vessel a few hours before. Ik falls off the main supporting pier, leaving a third of the channel crossing lurching out to nowhere. In the crew's dining room, the jolt is barely noticed.

It is Just enough to send the bottles of soy sauce skidding on the tables to fetch up against the catch rails, Wesley Maclntlre, in his 1974 Ford Courier pickup, realizes the bridge is falling out from under him. The 56-year-old Gulfport truck driver reflexively stomps on the brakes. But the tires are gripping only air. A dozen car lengths in front of Macln-tire, Betty McCoy, a 57-year-old South St. Petersburg teacher on the way to her job at H.S.

Moody Elementary School in Bradenton, wonders why there are no lights behind her all of a sudden as she drives safely off the span. Twenty-some car lengths behind Ma-clntire, James A. Pryor realizes the bridge is falling out beneath him. The 43-year-old foundry foreman, who lives in Seminole and commutes to Bradenton, jams the right side of his 1976 Chevrolet El Camino against the bridge railing, trying to stop, but it is too late. His car falls enveloped in a steel cage of bridge girders.

A 1979 Volkswagen Scirocco carrying Robert S. and Delores E. Smith of Pen-nsville, N.J., is a few car lengths behind Pryor's El Camino. It too is trapped in the falling bridge. All three survive the three-second fall but drown amid the tangle of steel as it sinks 50 feet to the channel bottom.

On the bow of the Summit Venture below, the boatswain and the lookout watch in horror as tons of steel roadway start to pancake down on them. One leaps for his life and keeps running until he is clear. The other hunkers beneath the protection of a huge anchor capstan and then faints dead away. The Courier follows its part of the span down and caroms off the bow of the Summit Venture, flipping into the water with a dazed but only slightly injured Ma-clntire still inside. Letting the wind swing the Pure Oil out of the channel less than a mile on the other side of the Skyway, pilot Schiff- 7:31 a.m.

Lerro orders 'the engine slowed further to "slow ahead." 7:32 a.m. Lerro, his binoculars squeezed tightly against his eyes, is searching desperately for a landmark in the streaming rain. Where is the bridge? he asks himself. The wind could be sliding the ship around in almost anydirection, scaling It like a leaf across a pond, and there would be no way to tell. Thirty seconds pass.

There are no voices on the bridge of the Summit Venture to compete with the howl of the wind and the drumming of the rain. Then, through a slight break in the deluge, Lerro sees a part of the Skyway roadway off to his right. The main span must be far to the left. Way far. Realizing he is out of the channel, Lerro orders the anchors dropped and rudder put over into a hard left in a desperate attempt to claw back to the channel opening.

He grabs the handle of the engine telegraph and rings it twice for an emergency hard reverse. 7:33 a.m. Windshield wipers flailing against the sheets of rain, wind-buffeted vehicles continue to cross the Skyway. Aboard the Summit Venture, the boatswain on the ship's bow manages to get the anchor on the left side into the water. The engine is beginning to go into reverse.

But the ship is still sliding implacably forward at better than 10 mph. And the seaward, southbound span of the Skyway is less than the length of a football field away. As quickly as it came, the brunt of the storm has charged on across the bay, leaving the visibility all too clear from the bridge of the Summit Venture. Lerro can only watch in disbelief as the ship, slowing but unstoppable, turning but not turning fast enough, takes its deadly aim. 7:34 a.m.

The Summit Venture's bow grinds through a pair of piers anchoring the south side of the main span of the Skyway's southbound lanes 800 feet to the right of the center of the channel. With its anchoring legs knocked out from under it, the cantilever bridge flexes spastically. A quarter-mile of the span Tm X. way, the full force of the storm runs into the Pure Oil, already going to anchor. On the bridge of the Summit Venture, Lerro is heartened by a report from Atkins that the ship is still on course.

Atkins knows this because he has managed to see the turn buoys on the radar scope for two sweeps before again losing the Image to the deluge of rain. Agonizing seconds pass in grinding tension for the pilots. The Chinese crewmen show no sign they think there is a problem. Lerro knows he is beyond the normal turning point and must immediately choose: Turn right out of the channel and perhaps be broadsided by the wind and be blown out of control into the Skyway? Turn left toward where the opening under the Skyway should lie? 7:30 a.m. Suddenly there is a telephone report from the lookout on the bow of the ship: "Buoy on the starboard (right) bow." Lerro immediately decides that the buoy must be No.

2A, which means he is passing his normal turning point but still in the channel. He decides to "shoot for the hole" the 800-foot-wide path under the Skyway between the main piers and tells Atkins to "come to the next course." Atkins relays the order to the helmsman. In ordinary cir-. cumstances, that would take the Summit Venture safely beneath the bridge. Lerro knows the turn is late, but he declines to oversteer since during the whole voyage the wind had been blowing on the starboard quarter (right rear) of the ship, pushing it to the left.

What he doesn't know is that the wind has shifted clockwise and now blows on the port quarter (left rear), pushing the ship to the right. I to 00 zontaliy across the decks in solid sheets. The Summit Venture is in the grip of the Skyway is just over a mile ahead. "t'Xt a.m. The storm races on and hits the Pure Oil on the other side of the Skyway.

Pilot Schiffmacher sees no point in plunging ahead when he can't see where he's going, especially with the bridge coming up. He decides to pull out of the channel, anchor and let the storm 7:28 a.m. The rain becomes so intense around the Summit Venture that the radar screen blooms into a smear of yellow, obliterating the individual targets such as upcoming buoys and the Skyway. Atkins loses the picture of No. 2A buoy which marks the gentle left turn into Cut A Channel which goes under the Skyway.

The ship will be at the buoy, less than 600 yards away, in less than 90 seconds. Weighing his options, Lerro decides he never be able to stop the ship before the Skyway without losing control of Jhe vessel. He rules out a hard left turn from the channel for fear that the fume-filled and explosive tanker Pure Oil would emerge in his path. He decides against a hard right turn out of the channel; fearing the wind would blow the ship broadside into the Skyway. That leaves the option of pressing toward We Skyway.

Lerro tells the still-si-lehtaptain to order the anchors made ready for instant release and for the lookout to keep a careful watch for a buoy that will mark the turning point. 7:29 a.m. Most cars on the Skyway' slow to a crawl as the visibility drops to a few feet in the slashing rain. The Greyhound plugs ahead at about 35 mph, passing at least a half-dozen cars. Among them is Richard Hornbuckle's yelldw Buick, which he is driving slowly iff" the right lane with the emergency flashers blinking.

'Less than two miles north of the Sky- The 7:06 a.m. The Summit Venture passes the Egmont Key lighthouse. 7:17 a.m. Rain starts falling harder around Summit Venture. before the bridge.

7:20 a.m. On the Good Sailor, now about four miles west of the Summit Venture and six miles west of the Skyway, pilot Evans has only a moment's warning before the violent squall hits. The crack of a lightning strike near the wheelhouse momentarily renders the crew deaf. With zero visibility, Evans points the bow into the wind and cuts the speed to ride it out by jogging in place. He won't think much of it until later, but when the sudden storm hit, the wind shifted from southwest to northwest.

7:21 a.m. Lerro decides to slow down and rings for "half ahead" on the engine telegraph. The ship starts slowing, but not much because of the boost from behind by both the flood tide and an increasingly stiff breeze, and it is still plowing ahead at better than 15 mph. 7:23 a.m. The rain and wind increase as the Summit Venture is passing buoy No.

16, obliterating visual observation of the buoy, which will be the last one seen for sure by anyone on the Summit Venture for the next 10 crucial minutes. Atkins closely monitors the radar, which continues to show the path between the next sets of buoys, and Lerro gives no thought to stopping to wait out the storm. The Skyway is 2.3 miles away 1 WW Bfejl1 Buoy 13 Lighthouse. Buoy12TBu0y14 i FLORIDA CNeflantf DumeNon Inverness Tampa across the state to the Palm Beaches, Fort Lauderdale and finally Miami. 7:06 a.m.

The Summit Venture passes the lighthouse on Egmont Key where Lerro had spent the night In the pilot station. The Skyway is six miles away. 7:10 a.m. The Summit Venture, just entering Mullet Key Channel, and the Good Sailor, an outbound bulk carrier being piloted by Evans, shape up for passing each other left side to left side. 7:13 a.m.

Rain begins falling around the Summit Venture. The National Weather Service radar in Ruskin shows much heavier thunderstorm activity 10 miles west of the ship and approaching fast. No warnings are issued, however. 7:17 a.m. Past buoy No.

12, it begins raining harder. Lerro becomes concerned about decreasing visibility. He tells the captain to send lookout forward. Then he adds a request for an "anchor watch," a man who will be prepared to quickly drop the anchors. The captain, who has just returned to the bridge and cannot see the bow of his ship 400 feet away, quickly Lerro takes over the conn from Atkins.

From, this point on, the Summit Venture is being navigated in violation of a rule that jays you must be able to see ahead at least twice as far as it will take you to stop the ship. In this case, visibility should be at least a mile rather than the hundred feet or so ahead that the pilot can see. I 7:19 a.m. Lerro spoie bound Pure Oil on the radar 2.3 miles on the far side of the Skyway and makes radio contact with Schiffmacher, the pilot aboard. Lerro figures that the Pure Oil will clear the Skyway first since the Summit Venture has three miles to go THE AST Str 1 Gulf of Mexico I Area I I 1 St PetersbursTVl step through dezvous with the Summit Venture.

Atkins, 34, is working the last of a required 30 days as a trainee before moving up to deputy pilot. 5:43 a.m. The Summit Venture's single propeller begins to turn slowly, nosing the 17,000 tons of ship slowly ahead to pick up the anchor. 5:48 a.m. The Greyhound pulls into Tampa.

6:20 a.m. Lerro and Atkins board the Summit Venture as the ship loafs along at dead slow, the pace of a brisk walk on land. The empty ship rides high in the water, and it's a long climb up the ladder. At the bus station in Tampa, the Greyhound, with a new driver, leaves for St. Petersburg, the next scheduled stop on the trip south.

At the port, a dozen blocks south, Schiffmacher has the Pure Oil undocked and is starting down the first channel. Up the bay, the bulk carrier Good Sailor, piloted by Capt. Earl G. Evans, is just passing under the Sunshine Skyway Bridge. 6:25 a.m.

The Summit Venture enters Egmont Channel inbound. The Skyway is 13 miles east and just over an hour away. 6:30 a.m. The National Weather Service radar at Ruskin shows intense thunderstorms some 70 miles out to the west, still racing toward Tampa Bay. Aboard the Summit Venture, Lerro' orders the engines advanced to half ahead.

6:37 a.m. Just before passing the second set of buoys Nos. 3 and 4 -iiu Egmont Channel, Lerro allows Atkins to "take the conn" and direct the ship while Lerro observes. The Skyway is a dozen miles to the east. 6:39 a.m.

As the Summit Venture passes buoy No. 4, Lerro sights the Dixie- Progress on radar as it nears buoy No. 8 32 miles to the east. But he cannot see tug's running lights. Over the radio, he finds out that the Dixie Progress is in a rain shower.

1 6:46 a.m. Lerro can see the lights Nautical Miles and even at half-speed ahead the ship is covering a little more than a mile every five minutes. J' 7:24 a.m. The morning rush vehicles at the Pinellas side toll lanes of the Sunshine Skyway continues unabated by the blowing rain. The Greyhound bust is among the vehicles creeping toward the toll booths.

In seconds it will pull away, accelerating to about 50 mph for. the six miles of causeway before theJ hump takes the southbound lanes of U.S. 19 150 feet up and over the main ship-' ping channel. On the Summit Venture, now almost exactly two miles west of the Skyway, the lookout and the anchor watch have just-arrived on the increasingly rain-lashed A bow of the ship. Visibility for them is -several dozen feet at best.

7:25 a.m. The full fury of the rampaging storm that struck the Good Sailor now catches up with the Summit Venture. What limited visibility there was vanishes as white water lashes hori- After thc clocked of west, "fit r. Venture The storm system, of Mexico, besnr Tampa P-y during COfilZ'a Lerro is searching frantically for a landmark. He sees part of the Skyway through a break in the clouds and realizes he is way off course.

He orders the anchors dropped, but it is too late. Thirty seconds pass and cars keep driving south toward the shattered span, their drivers still blinded by the rain. One driver, who has seen the red aircraft warning lights on top of the span tumble in front of him, backs down, the Skyway ramp, waving his arm helplessly as four cars and the Greyhound whisk past. Aboard the Summit Venture, Lerro and Atkins are spellbound as they see the headlights of cars arc off the end of the shattered Skyway toward the churning, white-capped water 150 feet below. One of the cars is a 1979 Chevrolet Nova driven by Leslie J.

Coleman a 52-year-old retired letter carrier commuting from St. Petersburg to a Bradenton real estate job. Another is a 1980 Ford Granada driven by Charles L. Collins, a 40-year-old -Tampa food broker on his way to a breakfast meeting in Bradenton. And yet another is the 1975 Ford LTD driven by Harry Dietch, 68, who was taking his wife, Hildred, to an appointment with her hairdresser in Bradenton.

Lerro grabs the microphone. day! Coast Guard! Mayday! Mayday! Bridge crossing is down!" North of the Skyway and safely coming to anchor, pilot Schiffmacher in the Pure Oil hears the radio call. 7:35 a.m. During this minute, the Greyhound and the 1980 Chevrolet Citation carrying a Pinellas Park couple, John J. Carlson, 47, and Doris I.

Carlson, 42, take the awful plunge. The 150-foot free fall accelerates their vehicles to 70 mph before they smack into the unyielding water. Drivers are still blinded by the whipping rain. There are no skid marks showing brakes were applied before they came to the abrupt end of the roadway. Aboard the Summit Venture, Lerro has to repeat his radio call before he gets an answer and then demands helplessly: "Stop the traffic on that Skyway bridge!" Richard Horhbuckle, driving at 20 mph, spots the terrible danger just in time and brings his yellow Buick to a slithering halt.

The car ends up perching askew on a downward-sloping steel slab of roadway 18 inches short of disaster. Hornbuckle, a 60-year-old St. Petersburg car wholesaler, and his three golfing companions, on the way to an early tee time in Bradenton, scrabble back to safety on the rain-slick steel. Hornbuckle walks back to the car to shut the doors, thinking through the shock that he should rescue his golf clubs from the trunk. His companions call him back to his senses.

His emergency flashers continue to blink. Running the battery down will be his only casualty this day. Wesley Maclntire somehow has struggled free from his sinking truck and 1 fought his way to the surface beside the ship. His fear now is that the Summit Venture will crush him as it drifts idly, its bow now shrouded in a bizarre garland of steel girders from the fallen Skyway. A World War II Navy veteran, he has been in peril in salt water before, but nothing like this.

He yells for help. Finally a crewman spots him and tosses a line. Maclntire gets his shoulders into the bowline's loop. A rope ladder is flung over the side. Maclntire lunges clear of the water but then collapses with his legs scissored around a rung.

He hangs on for dear life as five crewmen hoist him up to the safety of the ship's deck. He will be the only survivor of the plunge off the Skyway. Thirty-five people, including all 26 on the Greyhound, are dead. Writer: Bentley Orrick Graphics: Jim Bredeck, Tim Price and Ted Starr Photographs: Tribune files Editor: Nancy Gordon Sources: Government and court hearings, interviews The Bus The Greyhound, built in 1975 and driven over 700,000 miles, had seats for 43 passengers. It had 25 passengers, including a baby and six Tuskegee Institute students, aboard when it drove off the shattered end of the Skyway, performed an ungainly half-flip and landed on its roof at a speed of about 70 mph.

No one aboard, including the driver, 43-year-old' Michael J. Curtain of Apollo Beach, survived. squall grows even more ferocious. The sheets of rain and churning waves toss up so much water that the radar picture of the upcoming buoy is lost. Lerro thinks it is too late to stop, so he sails on, flying blind.

Before the storm hit, the wind was out of the southwest, pushing the Summit Venture to the te? About 200 miles due west of Egmont Key is a third point in a haphazard triangle. There the warm, moist tropical air mass that has been flowing to the northeast to dominate South Florida weather has developed instabilities that could grow into rare morning thunderstorms. It's a minute after midnight. It has just become Friday, May 9, 1980. 4 a.m.

The watch changes aboard the Japanese-built, Chinese-owned and Liberian-flagged motor vessel Summit Venture. The 609-foot-long phosphate carrier, cleanly painted and still new-looking in its fourth year at sea, is riding empty at anchor 10 miles out in the Gulf, where it has been for almost three days awaiting a berth after arriving from Houston. The Greyhound is driving steadily south between small-town stops from Dunnellon to Inverness. 4:20 a.m. A pilot boatman wakes Lerro so he can get about his day's work, which is, chalked in on the assignment board.

He is Unit 19. The ship is the Summit Venture, which is to go to a berth at the Rockport Terminal near Tampa to load 28,000 tons of phosphate rock bound for Korea. The trip will net the private association of Tampa Bay Pilots about $600. 4:30 a.m. The National Weather Service Radar at Ruskin shows an area of intense thunderstorms crossing the coastline 65 miles north of Tampa.

4:35 a.m. Lerro encounters misting rain as he walks from his bunk room to the pilots' reading room. But he can see a buoy flashing across Mullet Key two miles away, so he knows that visibility is not below his personal minimum for starting what pilots call a transit of the bay. 4:37 a.m. Lerro calls the Summit Venture on VHF radio, asking for a report on weather conditions around the ship.

The captain, Hsuing Chu Liu, replies In passable English that visibility is poor. Lerro advises him to wait out the drizzle, indefinitely postponing their scheduled 5 a.m. departure. 5 a.m. Lerro radios an Inbound tug, the Dixie Progress, and is told visibility has improved to three to four miles.

Up the bay in Tampa, Capt. John G. Schiffmacher has boarded the empty gasoline tanker Pure Oil. The veteran pilot notes a slight haze, but nothing to be concerned about, and starts directing the tugs to undock the Pure Oil for the three-hour journey to the Gulf. 5:10 a.m.

The captain of the Summit Venture reports better visibility. Lerro tells the captain to get under way. 5:30 a.m. The National Weather Service radar at Ruskin shows a line of intense thunderstorm activity has formed about 120 miles west of Tampa and is moving toward shore at a gallop. 5:34 a.m.

The Summit Venture's diesel engine rumbles to life. 5:40 a.m. Lerro, along with a pilot trainee named Bruce R. Atkins, boards a shuttle boat to the lighthouse. There they transfer to the larger pilot boat Egmont for the trip seaward to ren At dockside after the collision, remains of the Skyway are still draped over the Summit Venture's bow.

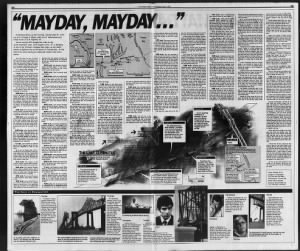

i 0-' THE MCMEOT OF DECISION When the Summit Venture's radar was blanked out by the storm near the turninB point to go under ttie Skyway, pilot John Lerro knew that it was too lata to stop. He considered three options: 11 MUTES Turn hard toft- Lerro feared he would be turning into the the final moments 3 Guanine Skyway disaster. The i.J. The lookout Tt to; reported a buoy has tanker Pure Oil, had actually anchored. BUOY close to the ship.

Lerro thinks it must be buoy No. 2A, his turning point. So he decides to try to steer under the Skyway. Buoy 1 A The option hs s7 which Turn hard right- Lerro feared the wind would blow the Summit Venture out of control and broadside into the took: Skyway 1,000 'X YARDS vi Buoy 2A The rain and wind pick up. The visibility drops.

The Summit Venture is being navigated by radar because the mariners can see only a few hundred feet at best. Even nearby buoy No. 16 is soon lost in the rain. Lining up with where the channel should be and shooting for the 800-foot opening under the Skyway. The main body of the storm catches up "with the Su mmit Venture.

Visibility drops to zero through the rain-lashed windows of the ship's bridge. On the bow, the lookout can see only a few dozen yards at best. Lerro continues on, navigating by radar. 1 500 1 YARDS' MJ If fi of the Dixie Progress now and surmises that the rain shower has dissipated or moved on. The Summit Venture has accelerated to better than 8 mph.

6:49 a.m. Lerro kicks the Summit Venture's engine up to full ahead to pass the lumbering tug, which is pushing a loaded barge. 6:54 a.m. Sunrise, but only by the clock. The gloomy rain clouds keep it almost as dark as.

night. 7 a.m. The Summit Venture takes the Dixie Progress near buoy No. 8 and begins a lazy right turn around the tip of Egmont Key. Capt.

Liu, seeing that all is routine, begins a 15-minute break in his cabin just below the ship's bridge. The ship, kicked along by a 1 mph current as the tide floods into the bay, is making better than 15 mph. 7:05 a.m. The Greyhound leaves St. Petersburg with 25 passengers, bound for Bradenton via the Skyway and then The Ship The Motor Vessel Summit Venture is a 609-foot bulk carrier built in Japan in 1976, owned and crewed by Chinese and flying the Liberian It sailed to Tampa 10 years ago to pick up a load of phosphate for the Far East.

The Summit Venture now plies a phosphate run between Australia and the Persian Gulf. I Phi The Survivors Richard Hornbuckle, 60, was on his way from St. Petersburg to play golf in Bradenton. He managed to stop his 1976 yellow Buick Skylark on the brink of disaster (left). He's retired now.

So's the car, inoperable but still in his I I I BUOY NO. ie The Bridge The Sunshine Skyway, most of it on causeways, spanned 15 miles of water linking the southern tip of Pinellas County with Manatee County. The first bridge, with two-way traffic, opened in 1954, replacing the 30-year-old Bee Line ferry. The twin parallel span, carrying southbound traffic, was opened in 1971 and destroyed in the disaster. Replaced by the new cable-stayed Skyway in 1987, the old Skyway spans serve as fishing piers.

Liu The seven for 1 'at; I "7 I 7 il testifying at Marine Board hearing. 37, I J-Lr Hornbuckle Wesley J. Maclntire, a 56-year-old Gulfport truck driver on his way to work, rode the falling Skyway down in his pickup truck. He was the only person to survive the fall from the bridge. He died of bone cancer last year.

i 'm Captain Hsuing Chu Liu, a 50-year-old Taiwanese and veteran of the Nationalist Chinese Navy, had spent years as a skipper the Hong Kong consortium that owned the Summit Venture. Testifying, he said piloting was a one-man job. He never said a word as the pilot pressed on through the storm. The Pilot Capt John Eugene Lerro, 1 was a non-drinking, hard-working, ambitious who had just good-old-boy after three years Venture was the Skyway- multiple sclerosis, The Greyhound, its back broken in the fall that took its 25 passengers and driver to their deaths, is hoisted from the channel. Lerro mariner been accepted into the network qf Tampa Bay Pilots as a deputy.

The Summit to have been his 789th trip under Ten. years later, disabled by he is a volunteer counselor. Maclntire The errant freighter chopped an anchor pier south of the main channel down to a stump, center, leaving girders dangling and tumbling 1,252 feet of span and southbound roadway into the mouth of Tampa Bay. The twin northbound span is undamaged. t.jffUl.AiJi.lS,.ifc-fSi AiiV.jffi,JIIVu.jtft..Ml 4 iifli iihiiidKuA, 0h fthitlnnA.

Am Jfci1rWli rfftih ifhiA Jhni.A ir rfmh A 1n rtSi fft- il fV nlfSi in" ii nr-Tui--AjSjfViLAiLln, 1 if if A A A m' A ftti rJ i A A rfm iik A Mi idfm Hn tf" II.

Get access to Newspapers.com

- The largest online newspaper archive

- 300+ newspapers from the 1700's - 2000's

- Millions of additional pages added every month

Publisher Extra® Newspapers

- Exclusive licensed content from premium publishers like the The Tampa Tribune

- Archives through last month

- Continually updated

About The Tampa Tribune Archive

- Pages Available:

- 4,474,263

- Years Available:

- 1895-2016