The Morning Call from Allentown, Pennsylvania • 2

- Publication:

- The Morning Calli

- Location:

- Allentown, Pennsylvania

- Issue Date:

- Page:

- 2

Extracted Article Text (OCR)

A-2 SUNDAY CALL-CHRONICLE, Allentown, April 12, 1981 rftv Av. VMtfiW- Hinckley: From North Dallas' 'Bubble' to Washington's Park Central Hotel submitted to newspapers in Denver, Hinckley wrote that he had worked as bookkeeper for a publishing house in Dallas which proved false when the paper checked and for a photography studio in Los Angeles, in the summer of 1976. The owner of the studio for which Hinckley claimed he worked, Richard Ellis, said a young man closely resembling Hinckley appeared at his shop sometime in 1977. "He seemed very young, perhaps a little out of high school. He said he wanted to take pictures of babies.

But we don't do that kind of work and he didn't have a portfolio," said Ellis. "He said he had taken many pictures before and knew what he was doing, but when Hinckley ever belonging to the party. And his parents have said through friends that photographs showing someone resembling him in a Nazi uniform are in fact not pictures of their son. According to leaders of the outfit, whose ideology includes the forced expatriation of blacks, Jews and avowed Communists, Hinckley joined the party in 1978 while in Texas. Michael C.

Allen, acting director of the extremist organization, claims he remembers Hinckley going to St. Louis to take part in a 1978 demonstration honoring the birth of George Lincoln Rockwell. Allen remembers that Hinckley was "flustered" and "bothered" and wanted to CHAPTER 2: Alone in west Texas The outsider moved to Lubbock In 1973, to a dusty, windswept college town in West Texas. There, at Texas Tech, an engineering-oriented University that accepts 99 percent of its applicants, he began a sporadic college career, dropping out at least three times, majoring in at least three different subjects, living in one nondescript garden apartment building after another. He started out interested in business administration, later majored in English, and still later developed a taste for history.

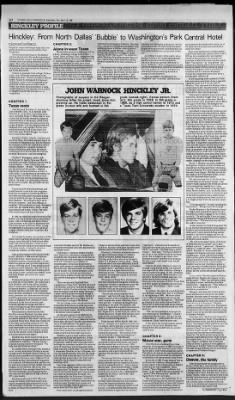

But there are other things, more than the records at Texas Tech, that grade (cutout right). Across bottom (from left): 8th grade in 1968, in 9th grade in 1969, as a high school senior in 1972 and a Texas Tech University student in 1974. Photographs of suspect in the Reagan shooting (after his arrest inset) show him growing up. He holds basketball in 4th grade (cutout left) and football in 5th i' J' Jf I Vi Vt fyf, vtVn ft vr i ft-, It, tl rJj'f .4" such attention that she took her name out of the phone directory and even moved into a motel for a while. Before she had become a college student, Jodie Foster had made a dozen movies and in 1976 had been nominated for an Academy Award for her portrayal of a 12-year-old prostitute in Martin Scorcese' violent urban fable "Taxi Driver." In "Taxi Driver" an alienated ex-Marine and would-be assassin played by Robert DeNiro masters a small arsenal of handguns, stalks a presidential candidate and in a climactic bloodbath rescues the young whore from New York's pornographic underworld.

At the beginning of the semester, Foster had received several letters from a man who signed his name as J.W.H. and John W. Hinckley. They expressed the stranger's love and devotion to her. The letters were a part of an incessant stream of fan mail she received.

Foster threw them into the garbage. Meanwhile in Lubbock, sometime in early September, Hinckley bought what was apparently his first gun, a blue steel .38 with a plastic checker-grip. He picked it up for $86 at the Galaxy Pawn Shop. The handgun was assembled by RG Industries in Miami from parts imported from Germany. A penchant for guns hardly strikes anyone as ominous in free-wheeling Lubbock where some university students carry guns to class and the pistol-packing frontier Texas tradition runs deep and long.

But Hinckley bought more guns. On Sept. 26, he visited the Snidely Whiplash pawnshop where he purchased two classic Saturday Night Specials cheap handguns also made by RG Industries. Sometime in early October, Hinckley set out for New Haven. He spent at least one night in the college town at the Colony Inn, signing his name and paying cash, according to manager Harry Gilbert, who is unsure of the exact date.

A maid who cleaned Hinckley's room said she found in the bed linen several pictures of Jodie Foster which she threw away. A bartender at the Top of the Park bar in the Park Plaza recalls that a man he now thinks was Hinckley spent about three hours one day last fall drinking, bragging that Jodie Foster was his girlfriend and showing bartenders clippings on the young actress. On Oct. 7, Hinckley arrived at Nashville Metropolitan Airport on Delta Airlines and checked into the Opryland Hotel, 10 minutes from the terminal. For some reason, possibly because it was cheaper, Hinckley moved the next night to the Downtowner Hotel, not far from the Tennessee State Capitol.

The next morning, Oct. 9, Air Force One touched down on the airport tarmac fthe country music capital of the world and Jimmy Carter stepped out, headed for a "town meeting" and a fund-raiser at the Opryland Hotel. Shortly before 1 p.m. on the 9th, three security guards stationed at a checkpoint gate on the south concourse saw a sandy-haired young man dashing toward them' to catch a 1 p.m. flight to New York.

He carried a small bag. "I'm running late," he said, thrusting his bag forward. "You gotta put this through. Evelyn Brannon of the Wackenhut Security Corporation motioned to Laura Farmer watching the airport luggage X-ray to check carefully. "He said he didn't have any guns," remembers Marjorie Pilklnton who watched the encounter.

"The man was very nervous. He couldn't keep still." As the conveyor carried the bag under the X-ray, Farmer discerned the metal shapes of firearms and immediately beckoned Officer John Lynch. Lynch opened the bag and discovered a handgun and two pistols as well as handcuffs and a box -of 50 hollow-point bullets. "He told me he wasn't aware of the laws of Tennessee that he couldn't carry guns without a Lynch said. "He said he was sorry a couple of times." At 1:12 p.m.

John W. Hinckley Jr. was arrested and charged with illegally carrying a weapon, a misdemeanor. Lynch took him downtown while another police officer telephoned the FBI in Nashville to notify them of the arrest. On the way to the station, Lynch recalls, Hinckley said he was returning to school at Yale University from his home in Texas and that he planned to give one of the guns to a friend, sell the second and perhaps keep the third.

At the station, Hinckley appeared before Judge William Higgins who vaguely recalls the encounter. "There was something about him going to school, something about law enforcement," Higgins said. "That's what he said he was studying. To me it was a satisfactory explanation. The guns, that were still in their factory boxes and had never been fired, were con- fiscated.

Hinckley spent 30 minutes in a cell while a jail trusty processed his $50 bond and the $12.50 he had paid for court costs. Lynch drove him back to the airport. Hinckley caught a 5:20 flight to New York. The episode, law enforcement authorities now believe, was an experience that would persuade the young man to travel by bus the next time he desired to transport his guns. Four days later, Hinckley had returned to Texas.

He walked into Rocky's Pawn Shop on 2018 Elm Street on the east end of downtown Dallas. The bumper sticker plastered over the front door reads "Guns Don't Cause Crime Anymore Than Flies Cause Garbage. Hinckley bought two RG pistols like the ones that had been confiscated in Nashville. The serial number on one of the Saturday Night Specials was L-73132. Almost five months later, at 3:30 p.m.

on March 30, Isaac (Rocky) Goldstein, the 70-year-old owner of Rocky's, got a call from agents of the Bureau of Alcohol. Tobacco and Firearms who said the gun had been used in an attempt to assassinate President Reagan. CHAPTER 4: Denver, tho family After he purchased two handguns from Rocky's Pawn Shop, John Hinckley traveled to Colorado where his family had resettled In a Denver suburb. This wes the start of a five-month period in which Hinckley spent time In squalid motels, when he could have been in his parents' luxurious house, and haunted a high school he had never attended. He applied for jobs, and his father at one point even took cheer in his aimless son's apparent resolve to settle in and look for work.

See HINCKLEY Page A3 Continued From Page A 1 his guitar, empty hamburger bags and a tew pieces of furniture covered with the West Texas dust. The evolution that began in The Bubble and was played out in the seediest sections of towns across the country climaxed in a violent moment one rainy spring afternoon in Washington. This is the story of a man who left his childhood in a fairy tale suburb and embarked on a journey that was marked by alienation, a gun fetish and failure. Failure to graduate from college. Failure to get a job.

Failure to measure up to his brother and sister. Failure to connect with his father. Failure to distinguish life from art. And finally, failure to be recognized in the affections of teen-age movie star Jodie Foster, for whom he had developed a monumental obsession. His odyssey ended in what he thought would be the ultimate act of recognition.

CHAPTER 1: Texas roots John Warnock Hinckley Jr. was born May 29 in Ardmore, to Jo Ann and John Hinckley Sr. At the time, his brother Scott was 5, his sister Diane, 2. When John Jr. was 4 years old, the family moved to a house on Caruth Street In a community called North University Park about six miles north of the center of Dallas.

It is the stepping stone into Highland Park, and together the two communities form the Park Cities which last November gave Ronald Reagan the largest vote of any Dallas suburb. Hinckley's father, John was born and reared In Tulsa. He studied engineering at the University of Oklahoma and, until he founded the company in 1970 that made him a millionaire, he worked for a number of small oil firms in Oklahoma and Texas. He was an archconservative who divided his interests between Christianity and free enterprise. Charles V.

Westapher, pastor of St. Michael and All Angels Episcopal Church, remembers the elder Hinckley and his wife as church leaders. "I don't think they ever missed a Sunday," he said. "The Hinckleys fit into the pattern of the parish redneck Republican, ultraconservative, as I am. A solid family.

I can see them in my mind's eye standing there with their children around them. There was nothing outstanding about John Jr. He wasn't an outstanding achiever. He was not in trouble. He just fades Into the mist of time." Young Hinckley played basketball and traded baseball cards with other neighborhood boys as a pupil at Armstrong Elementary.

But even then, there was such a sharp contrast with his siblings. He languished in their shadows. "He seemed to have an inferiority complex," said Toni Johnson, a neighbor. "He was always so quiet. He used to come over for vanilla wafers and he would help himself and not say a thing.

The other kids would always talk more than him." In 1966, the Hinckley family arrived in The Bubble, moving into a two-story vellow-brick house, with a swimming pool ana a private Coke machine, in the heart of Highland Park. The house was set on Beverly Street among the mansions of millionaires such as silver magnate Herbert Hunt and Texas Gov. Bill Clements. Surrounded by Dallas, the residents in The Bubble have long been protected from social change, from life as it is lived in most other towns and cites in America. Crime is minimal, and the town's police force spends much of its time simply cruising the streets to remind the residents of their safety.

After graduating from McColloch Middle School, Hinckley In 1969 entered Highland Park High School, which boasts such an excellent academic reputation that it is con- sidered as good as many private preparatory schools. Over the years, it has produced such graduates as Bill Clements, who still lives in the neighborhood, Nobel-prize-wlnning physicist James Cronin, football stars Bobby Layne and Doak Walker and movie star Jayne Mansfield. Religion dominates life in the high school as it does life in The Bubble. The school has a daily devotion, and at pep rallies, football players often come forward to offer extemporaneous prayers. At Highland, not only do students own their own cars, they consider those who don't abnormal.

It is a school where social pressures are often more severe than academic pressures. Caste systems established at Highland Park continue for years afterward, in the form of sorority and fraternity groups in college and even in weekly bowling outings when students return to Highland Park to settle as adults. When handsome, blond-haired John Hinckley entered Highland, his older sister Diane was emerging as one of the most successful students in the school. A pretty and exuberant Texas belle, Diane was chosen one of the eight outstanding seniors in 1971. She was a candidate for homecoming queen and head cheerleader at a school where students run for the title and are selected by popular -vote.

In the insular world of Highland Park, few achievements rank higher. Hinckley was never a part of this world. He achieved nothing remarkable and thus was condemned to obscurity. "He was normal," recalled classmate Beverlv McBeath. "Nobody paid anattention to him." In a school where normality was almost a curse, no one remembers Hinckley's attending high school weekend rituals or dating.

He seems to have passed from freshman to senior year without leaving a trace. Highland Park yearbooks portray a succession of snapshots of a clean-cut, Ail-American kid, and they list his activities as Spanish Club, Rodeo Club and Students in Government. But no one who participated in those groups remembers him. His own classmates recall his older sister, who was married right out of high school in 1971, more readily. Hinckley graduated in 1973.

When his family left Dallas in 1974 and moved to an equally prosperous and protected life in an affluent suburb of Denver, he stayed in Texas to enroll at Texas Tech University in Lubbock. i s4 4 'vA, fh I began to ask him some questions it was clear he did not. He didn't even know the difference between depth of field and field of focus." Eventually, Hinckley wandered eastward and again took up his studies in Lubbock. History professor Joseph King recalled Hinckley as the fellow who sat by himself In King's U.S. Economic History class.

"While everyone else in the class exhibited a kind of camaraderie, he always sat alone, surrounded by empty chairs," said King, who gave Hinckley an A on a paper he wrote about American slavery. "Even during humorous moments, he continued to gaze at me attentively, taking notes." Off campus at Texas Tech. the few persons who remembered seeing the withdrawn young man included a maintenance man who cleaned the apartment building in which Hinckley lived and the appliance dealer from whom he rented his televisions. "His attitude and personality were strained," said Calvin Wynne, the maintenance worker at the University Arms apartment complex who spoke to Hinckley there twice last fall. "It seemed as though he had something on his mind.

He wanted to talk about it, it seemed he wanted to find someone to tell it to. There was a nervousness about him. Hyperactive, is that what you call it? He moved about a lot. He got more anxious, more hyper as the conversation wore on, like he wanted to do something about it." From January 1978 to July 29. 1980, Don Barrett, manager of an appliance rental store in Lubbock, rented Hinckley a television four times.

Barrett said Hinckley had been in the office dozens of times, either renting or making his payments. "He would say hello and so forth but as far as initiating a conversation, he didn't," Barrett said. Twice, Barrett said, he visited Hinckley's apartment to deliver televisions, and found that the student had no silverware, little furniture and nothing on the walls of his room. His credit was good enough, though. Hinckley was able to rent a television on only his signature the last three times he dealt with Barrett.

The last day Hinckley returned a television set to the store he was short two dollars. Barrett said the young man dutifully ran off to collect the deficit. "John is honest," Barrett said. "If he walked in today. I would probably rent him a television set.

When I heard he was in court in D.C. addressing the magistrate as 'yes sir! and 'no that sounded like Jonn." It isn't yet clear when, or even if. the drifting Texan Joined the neo-Nazi membership of the American Socialist Party of America, another strange and twisted world In itself. Law enforcement officials and the Anti-Defamation League have no record of "fight when several thousand Nazi demonstrators ran the marchers out of the St. Louis park.

"He liked being a storm-trooper," Allen said. "You have to like it to put on one of our uniforms and do the things we do. But we began to get reports that Hinckley wouldn't conform to our program. He kept trying to get people to go out and shoot people. It got to the point, Allen said, where the strange young man he thinks was Hinckley was suspected by other members of being a federal undercover agent.

In 1979, Allen said, the man was expelled. While Hinckley's connection to the party remains uncertain, it is known that he took a course on Modern Germany in the summer of 1978 at Texas Tech and wrote papers on German concentration camps and "Mein Kampf," Hitler's autobiography. In Lubbock, the owner of a used-book store said Hinckley visited him "four or five times" at the beginning of 1980. "He never talked much, which is unusual for any of my customers." said Lonie Montgomery. "He would go directly to that section where I had the World War II books and stand and go through the books and he stayed 30 minutes to an hour each time.

"The last time he Was in. he bought the two-volume set of 'Mein I couldn't understand why his type the way he was dressed and all could afford $30 for a two-volume set. I didn't see him after that." At the end of the second summer session last year at Texas Tech, Hinckley was dropped from the student rolls for non-payment of fees. CHAPTER 3: Movie star, guns After Hinckley abandoned his college education in the summer of 1980. he turned to a new obsession that lured him north to New Haven and to other towns around the country.

The drifter who had so few real friendships in his life had become Involved In a fantasized relationship with movie starlet Jodie Foster. In the fall of 1980, Foster entered Yale as an 18-year-old freshman. She published a breezy article in the college Issue of Esquire which said she was trading the "disco dresses, People Magazine, and Santa Ana winds" of her starlet's life In Los Angeles for "good ol' New Haven grime" and the collegiate life at Yale University. The magazine hit the stands Sept. 20.

as Foster was settling into her room in the gothic brownstone Welsh Hall on Yale's Old Campus, a section reserved for freshmen. Knots of would-be suitors sometimes gathered and knocked on the dormitory door. Foster drew show how Hinckley had left The Bubble only to become enveloped in his own disconnected and lonely world. He became a wanderer and an invisible man. Some local merchants, among the few townsfolk who remember him, recall that he would head out each morning on a methodical stroll for a late-morning breakfast of cheeseburgers.

He seemed to have only a guitar and a series of rented black-and-white television sets. His apartments, according to the few people who visited him there, were barren, save for a few pieces of furniture, tightly drawn window shades, the Inevitable dust and the bluish glow of the black-and-white. There were former Highland Park classmates at Texas Tech, but they lost touch with Hinckley and never saw him on campus. He took a variety of college courses, Including three journalism and three music literature classes, and his grades were good enough to keep him in school. One semester, the fall of 1977, he made the university Dean's List by maintaining an average of or better.

But his college career was an unsustained, scattershot thing spanning seven years and including three mysterious breaks. During at least one of these breaks, Hinckley ended up in the nation's movie capital. As the nation prepared to celebrate Its bicentennial in 1976, Hinckley left Lubbock and wandered to Hollywood, where he lived In Room 348 at Howard's Weekly Apartments on North El Centro Street. The green-stucco building was only about a mile from Hollywood and Vine streets, a corner symbolic of movie fame and success and money, but it might as well have been light years away. Hinckley's part of town was tree-lined, sunny and relatively well-cared-for.

It was also a haven for drugs, homosexuality and prostitution. Several other small apartment buildings for transients occupied the area and a row of small bars and pornographic bookshops was only a block away. The only tenant to remember Hinckley Is Larry Ehmpke, a 51-year-old forklift operator who said the young man who lived across the hall from him five years ago had a heavy face, short hair and a mustache, but he doesn't remember ever speaking to him. Very little is known of Hinckley's life in the underside of Hollywood, so many years and miles from The Bubble. Only in the paper trail of apartments leased and items pawned can traces of his existence be found.

At a pawn shop called the Hollywood Collateral Loan Association, located only a few blocks away from Howard's Weekly Apartments, an employee went through shop records and found that Hinckley pawnecf a stainless steel watch there for $15 In June 1976. Four years later, on job applications he.

Get access to Newspapers.com

- The largest online newspaper archive

- 300+ newspapers from the 1700's - 2000's

- Millions of additional pages added every month

Publisher Extra® Newspapers

- Exclusive licensed content from premium publishers like the The Morning Call

- Archives through last month

- Continually updated

About The Morning Call Archive

- Pages Available:

- 3,111,532

- Years Available:

- 1883-2024