The Observer from London, Greater London, England • 95

- Publication:

- The Observeri

- Location:

- London, Greater London, England

- Issue Date:

- Page:

- 95

Extracted Article Text (OCR)

4 exciting project it was going to be and I phoned them up when I got home. I realised it was the thing I had to Tim Mace a 35-year-old Army major was in the middle of training for the National Parachute Championships but called the hotline: 'By the time the paperwork arrived it was the day before the Nationals, so I ended up writing my application form and composing all the tough answers required in the midst of the National Parachuting Championships. That was quite hard work, staying up to about one in the Nearly 1 3,000 applications were received, and most were rejected immediately. A total of 35 'survivors' were then subjected to tests at a BUPA clinic near King's Cross. From this, four finalists were announced on 5 November: Helen and Tim, plus Navy pilot Gordon Brooks and engineer Clive Smith.

This quartet was sent to Star City, the cosmonaut training centre situated 25 miles north-east of Moscow, where a team of 40 doctors performed even more tests. Three weeks later, Helen and Tim were chosen live on a national television programme presented by Anne Diamond. The show had all the tacky hallmarks of a low-budget quiz show, lacking any of the gravitas appropriate for a serious scientific endeavour. Nor did the relentless hype stop then. Once selected, both Helen and Tim had anticipated publicity, but not of the numbingly banal variety produced by Juno.

Former In a few days, more than 30 years since the first man flew in space, a British astronaut should, at last, take his or her first steps to the stars. Our first starperson will take a lift to the top of a booster designed in the Sixties; strap her, or himself, into a capsule of equally uncertain pedigree, and prepare to blast off from the windswept misery of Baikonur cosmodrome. Once in orbit, the representative of a nation that once prided itself on the white heat of its technology will carry out a few brief but vital tasks: make the coffee on request, keep out of the way and generally remain quiet unless spoken to. Indeed, the medical complaint most likely to affect our astronaut will be swollen wrists from being smacked every time she or he touches a keyboard or button. Or at least, that is how Soviet space officials joke about the mission.

So much then for the country that gave the world the jet engine, the idea of communication satellites and, most importantly, Dan Dare. Like an impoverished, Third World nation dependent on the technological charity of others, we will slink into space as part of an enterprise that would embarrass Arthur Daley. It is a thoroughly depressing state of affairs, though few will hesitate in wishing a bon voyage to Helen Sharman or her back-up, Tim Mace, if he is chosen to replace her at the last minute. Both have suffered stoically and mightily for the privilege of becoming Britain's astronaut. They have undergone the public humiliation of involvement in Project Juno's ridiculous television game-show selection process.

Then they experienced 10 months of life in limbo following the collapse of Juno, while recriminations and rumours abounded. And, finally, Ms Sharman and Major Mace have had to go through another year's exile and boredom in Russia, where they have taken part in a virtually worthless training programme. So how did this farrago begin? How have the nation's space aspirations been reduced to such an insubstantial and gimmicky level? In fact, the genesis of Project Juno came at a time when the British Government had turned its back on space endeavours and the Soviet space programme was suffering economic convulsions. The Soviets needed hard currency, our scientists wanted a man, or woman, in space. So the indefatigable Heinz Wolff of Brunei University set up a private company backed by the Moscow Narodny Bank to buy a place on Mir, the orbiting space station.

Two dozen experiments were put forward as justification for the project. The mission was announced at the end of June 1989. Full-page newspaper advertisements declared Astronaut Wanted. No Experience Necessary', while the text assumed a breezy tone: 'The British astronaut will become a full member of the Anglo-Soviet flight team fulfilling the tasks of an astronaut as well as conducting a series of scientific experiments. The mission is carrying no passengers." Helen Sharman a 27-year-old non-smoking vegetarian who was studying for a PhD on the luminescence of rare earth ions was one of thousands who heard about the project on her car radio as she travelled home.

She jotted down the telephone number while waiting for traffic lights to change. 'At the time I thought what a really confectionery research scientist Helen Sharman becam'e 'The girl from Mars who is reaching for the stars' while Major Mace had to endure lines such as 'Ground control to Major Tim'. In the meantime, Juno officials maintained an unblinkingly confident posture. There would be no trouble in raising the 1 6 million needed for the mission. Of this total, 6 million would go on training and UK costs, they said, while the remainder would be paid to Russia for travel on board Soyuz, and a week's stay on Mir.

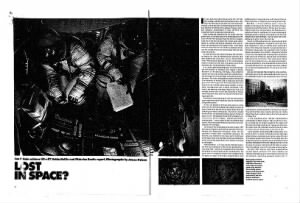

Juno's constant refrain stressed that negotiations were going on with 'a number of interested parties' although, under pressure, spokesmen and women agreed that no firm backers had yet been found. At the same time, the project did nothing to quash rumours of battles between national newspapers who were bidding millions for the pleasure of exclusive monitoring of the flight or airlines who were fighting to carry the returning astronaut home. By early 1990, however, only three companies had actually signed contracts: ITV, Zeon watches and Mcmtek International, part of the Memorex Group. The last planned a marketing approach replete with Main picture: British hopefuls Tim Mace (left) and Helen Sharman in the flight simulator at Star City, Moscow. The training centre boasts several portraits of Yuri Gagarin (left and above), the first Soviet cosmonaut and first man in space Can Britain achieve lift-off? Robin McKie and Nicholas Booth report.

mm Photographs by James Nelson 32.

Get access to Newspapers.com

- The largest online newspaper archive

- 300+ newspapers from the 1700's - 2000's

- Millions of additional pages added every month

Publisher Extra® Newspapers

- Exclusive licensed content from premium publishers like the The Observer

- Archives through last month

- Continually updated

About The Observer Archive

- Pages Available:

- 296,826

- Years Available:

- 1791-2003