The Montgomery Advertiser du lieu suivant : Montgomery, Alabama • 43

- Publication:

- The Montgomery Advertiseri

- Lieu:

- Montgomery, Alabama

- Date de parution:

- Page:

- 43

Texte d’article extrait (OCR)

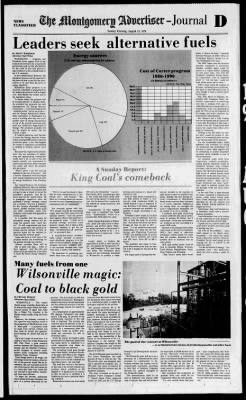

JBl0tt00iliers aiwfea Journal HD NEHS CLASSIFIED Sunday Morning, August 19, 1979 Leaders seek alternative fuels Energy sources U.S. energy consumption by source Cost of Carter program 1980-1990 (In billions of dollars) SOURCE: The White House fs OU49 7 I 80-0 i 70.0 50.0 Water 4 30.0 I 1 20.0 I 15,0 Nuclear 4 I 2.0 V' 1.0 A Coal 18 tol gas 25 I SOURCE: U.S. Dept. of Energy data a 3 a 50 a By PEGGY ROBERSON Advertiser Staff Writer WASHINGTON Congress and President Carter appear to be of one mind on the necessity for a mammoth government push to find alternatives for the crude oil that now gives foreign producers a life-or-death hold on the U.S. economy.

In the months ahead, however, the legislative process can be expected to bog down on how to pay for the alternatives to oil and what the price of energy should be. Multiblllion dollar projects to be financed, subsidized or guaranteed by the federal government will be fought over, both behind the scenes and in the legislative arena. To decide where the projects will be located and how to finance them, the president has proposed two new superagencies, the Energy Security Corporation to be bankrolled by the "windfall profits" tax on oil profits and the Energy Mobilization Board. Many lawmakers in Washington are wary of creating what they see as yet another layer of energy bureaucracy on top of the already enormous and, some say. ineffective Department of Energy.

The president probably will get the boards he wants, but not without a fight. If Congress approves, over the next 10 years the Energy Security Corporation would get $88 billion to meet its production goals, a sum that boggles the minds of legislators accustomed to dealing in millions almost every day. But powerful congressmen and senators who are members of authorizing and appropriating committees would have a lot to lose if the new boards actually are empowered to make major decisions about who gets the money and where the projects will be placed. "That's where I see the real gut fighting for the rest of the year," said a former Alabamian who has helped draft energy legislation and now edits an energy newsletter from Washington. Sen.

Donald Stewart, the freshman Alabama Democrat who is a member of two of the several committees that will get to take a whack or two at the president's proposals, said he believes they will be "pared down." He is grudgingly supportive after the president's energy message turned out to include "scarcely a footnote" for his favorite alternative energy source, alcohol distilled from grain and other renewable farm commodities, to be mixed with gasoline to create gasohol. Is it possible that the quest for alternative energy sources will become the nation's next "pork barrel?" Or will congressmen and senators put aside their own political interests and the welfare of their respective states for the national interest and the common good? Some who have a close view of the situation believe the scrambling for the goodies already has started. Stewart concedes there will be "lots of pulls and some of them regional," over the jobs and dollars to be parceled out in an effort to make the nation energy plenty of others out there," conceded Edward Williams of DOE's Office of Technology Impacts, quoted in a recent Washington Post story. The DOE report used the strictest possible standards to determine whether synfuels plants could be placed in a county without violating air and water laws. (Not even the president's hoped-for Energy Security Corporation, with its expected power to "cut red tape," could set aside clean water and air laws.

DOE's study found 159 counties in 22 states, including some in Alabama, that have at least 400 million tons of coal, enough to feed a synfuels plant for 25 years. Rep. Tom Bevill of Alabama, impressed with Tennessee Valley Authority's experiments in converting coal into a medium BTU gas, included $5 million for design work on a commercial scale coal gassification plant for TVA in the bill reported by his energy and water resources appropriations subcommittee. Sen. Stewart did a little trading over on the Senate side of Capitol Hill to keep the $5 million in that body's version of the bill.

It has passed both houses but awaits final action after going to conference. Nothing in the bill spells out that the plant would be located in Alabama, if it is eventually built, but that is an obvious hope of the sponsors. For the foreseeable future, while engineers and scientists are trying out promising new technologies for alternative fuels, other experts will be attempting to answer important questions about tradeoffs in cost to the environment. Air pollution could result from large-scale synfuels production. Carbon dioxide emissions would be multiplied because some synfuels processes, like the one at Wilsonville, require that the fuel be burned twice.

High levels of carbon dioxide could blanket the earth and retain heat, a situation environmentalists call "the greenhouse effect." Sulfur and nitrogen emissions can cause "acid" rain, which is polluted rainfall that can damage crops and cause water pollution. In the arid West, a large demand for water, essential to synfuels production, could create serious problems. Plant discharge could not be absorbed by the few streams and lakes without raising pollution to a dangerous level. Solid waste, that could include toxic materials, could cause a massive disposal headache. Land disruption from strip mining of coal could lead to water pollution, soil erosion and loss of farm land.

Liquid coal is a cancer causer and could affect workers and those using or hauling the fuel. But with all the problems some which appear to be almost insurmountable the nation has finally found a direction, however tentative. President Carter used energy as his rallying cry for "a rebirth of the American spirit." "On the battlefield of energy," the president said, "this democracy which we love is going to make its stand." A inlay King CoaPs Report: comeback 9 2- a 3 1 tatively decided on 42 counties in eight states as sites for synthetic fuel plants. Whether the new Energy Security Commission or Mobilization Board would overturn those decisions is, of course, unknown. Alabama is not among them, an oversight the state's congressional delegation can be counted on to try to remedy.

A synthetic fuels plant could bring in about 4,000 new jobs and an investment of perhaps $2 billion, but it could cause "social and environmental" problems as well, according to a recent DOE study. Because of the damage such a plant could cause to the local environment, DOE's first round of selections eliminated synfuel plants for more than 100 counties, including all the possible sites in Alabama and six other states. DOE said synfuel plants could be built in Colorado, Illinois, Montana, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Texas, West Virginia and Wyoming. "That doesn't mean there aren't 100 years old. Remember "coal oil," that smelly, dirty, low-grade gas used to fire ovens and street lamps after the turn of the century? It came from coal, but the demand for it ended with the advent of cheap electricity and natural gas.

"Liquefaction" is what happens when coal is converted into liquid form. "Gassification" refers to a process that turns coal Into a gas. Small liquefaction plants at Wilson-ville, about 100 miles north of Montgomery, and at Fort Lewis, are using variations of the process to squeeze three barrels of oil or a solidified form of liquid coal from every ton of coal. Larger plants, to produce the equivalent of 20,000 or more barrels a day, are planned for Morgantown, W. and Owesnboro, near large coal fields.

The Owensboro plant would use the technology developed at Wilsonville to produce a clean- removed from the wash solvent from the distillation filter can be recovered Many fuels from one Wilsonville magic: burning solid instead of a liquid substitute for coal. Each of these plants is expected to cost $700 million to build. A commercial plant producing 50,000 to 100,000 barrels a day is expected to cost $2 billion to $3 billion, although accurate estimates are probably impossible to make, according to authorities. President Carter wants 2.5 million barrels a day in substitute fuels by 1990, to help him keep his promise that "this nation will never use more foreign oil than we did in 1977 never." It is an ambitious and costly undertaking. For while the Oil Producing and Exporting Countries (OPEC) are pushing crude oil prices to $22 a barrel, synthetic fuel would cost still more, from $27 to $45 a barrel.

The president and many in Congress believe that price may yet turn out to be a bargain by the end of the century. The Department of Energy has ten r- 3 I I The goal of the venture Research and Development Administration. The Wilsonville plant will serve as a prototype for a demonstration plant proposed for construction to determine whether the system can be commercially successful, according to Bob Hart of Southern Company Services, general managers of the Wilsonville plant. "The demonstration plant to be built in Kentucky will process 6,000 tons of coal per day and will produce SL. "There's no question about it, there will be some competition for it (the energy pie)," said Stewart.

"But when we're talking about the national interest we must assume1 elected representatives will act responsibly." Not everyone agrees with him. "It's already reached the scrambling stage, with very little concern for the national interest," said one government agency official who asked not to be quoted by name. "I think we've learned through previous crash projects, though, that it takes a little excessive spending to get the job done." He believes not all "pork barrel" is necessarily bad. A multibillion-dollar synthetic fuels (called "synfuels" in government shorthand) program is at the heart of the president's energy plan. Actually, the term "synthetic fuels" is not accurate because they come from coal, a natural raw material.

The know-how for producing synthetic fuels from coal is more than process. (The first batch in 1973 was mixed with creosote oil. Hydrogen is added to the slurry of coal and solvent and the preheated mixture is fed into a single-stage reactor for nearly 30 minutes. At a temperature of approximately 875 degrees Fahrenheit and under nearly 1,700 psig, 94 percent of the carbonaceous material in the coal feed is dissolved. The process also converts about 60 percent of the organic sulfur in the coal into hydrogen sulfide.

In a commercial plant this by-product would be further processed and recovered for sale as elemental sulfur. From the reactor the liquid is again pressurized to release gas phases and the liquid slurry is subjected to a solids separation step where undissolved solids are removed. The remaining liquid goes through what Gene Boykin, technical director of the plant, describes as the "biggest legal still in the county," where process slurry is recovered overhead and recycled to slurry the coal feed. The solid that settles to the bottom of the still is the solvent refined coal product which solidifies at 350 degrees F. In liquid form it is similar to thin oil and as it solidifies it is broken up on a water-jacketed vibrating conveyor.

Researchers believe the dried solids Coal to black gold r' I By PHYLLIS WESLEY Advertiser State Editor WILSONVILLE The wizard Merlin wears a hardhat these days as he weaves his magic within the multicolored myriad of pipes that looks like a Tinker Toy creation in the Shelby County woods along the Coosa River. However, the alchemy involved in this operation may someday result in the production of 100,000 barrels a day of "black gold" a synthetic crude oil made from solvent refined coal that could be turned into gasoline, home heating oil, diesel fuel and jet fuel. But it isn't magic at work here. It is reality in the form of the Wilsonville SRC Pilot Plant, a joint research venture between the Department of Energy and the Southern Company, parent company of several southeastern utility companies including Alabama Power Company. Even though there is no magic, the technology involved makes a description of the process sound like an incantation.

The raw coal goes in at the rate of six tons per day and comes out in a form that looks very much like raw coal but is more brittle, cleaner, and more heat -efficient. Jo begin the process, pulverized coal is mixed with approximately two parts of a solvent generated by the in a commercial plant to supply the hydrogen required by the process. The process removes 98- to 99-percent of the ash in bituminous coal and nearly the same percentage of sulphur, according to research reports. It will not work on anthracite coal, however. Heating efficiency, or BTUs, per pound of coal is increased from 12.000:BTUs per pound of raw coal to 16,000 BTUs per pound of SRC.

Basic engineering designs for SRC processing were begun as early as 1962 by the Spencer Chemical Company, under the sponsorship of the Office of Coal Research of the U.S. Department of the Interior. The Spencer Company was bought by the Gulf Oil Corporation and research was continued by a coal mining subsidiary of Gulf Oil. The first SRC pilot plant was built in Fort Lewis, Washington, and could process 50 tons of coal per day. The Wilsonville plant was designed, built and is operated by Catalytic, in 1974 after two years of research by the Edison Electric Institute and the Southern Company.

The plant is located on the site of Alabama Power Company's Ernest C. Gaston Steam Plant, sponsored jointly by DOE and the U.S. Energy 'V at Hilsonville to find alternate means of producing gasoline and other fuels pect," said Congressman Bill Nichols, who toured the Wilsonville plant last week. "I'm really excited about the potential for coal especially with the amount of coal in Alabama." "It's not going to be cheap energy but Americans are ready to find an answer to replace OPEC fuels," Nichols said. "I believe most of us will be using gasoline that comes from coal one day.

Americans believe we can take care of ourselves, and we can." the equivalent of 20.000 barrels of oil per day," Hart said. "If we can prove that it is successful, a commercial plant could process 30.000 tons of coal per day producing the equivalent of 100,000 barrels of oil per day, 80 percent SRC, eight percent light oil, seven percent medium oil and five percent heavy oil." Hart estimates that production of gasoline from coal could be accomplished within the next decade. "I'm very excited about that pros i.

Obtenir un accès à Newspapers.com

- La plus grande collection de journaux en ligne

- Plus de 300 journaux des années 1700 à 2000

- Des millions de pages supplémentaires ajoutées chaque mois

Journaux d’éditeur Extra®

- Du contenu sous licence exclusif d’éditeurs premium comme le The Montgomery Advertiser

- Des collections publiées aussi récemment que le mois dernier

- Continuellement mis à jour

À propos de la collection The Montgomery Advertiser

- Pages disponibles:

- 2 091 649

- Années disponibles:

- 1858-2024