The Santa Fe New Mexican from Santa Fe, New Mexico • Page 122

- Publication:

- The Santa Fe New Mexicani

- Location:

- Santa Fe, New Mexico

- Issue Date:

- Page:

- 122

Extracted Article Text (OCR)

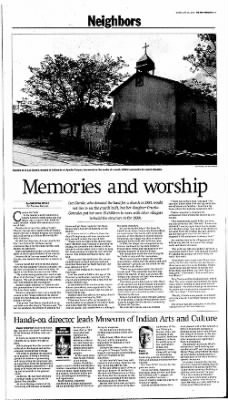

Sunday, June 30, 2002 THE NEW MEXICAN E-5 Jane New Mexican Nuestra de la Luz Church, located at Canoncito at Apache Canyon, has served as the center of a small, faithful community for several decades. Memories and worship By CHRISTINA BOYLE For The New Mexican uentos delValle In the hamlet called Canoncito at Apache Canyon, small hands and big hearts built a church that would for many decades remain the community's center of faith. Nuestra de la Luz (Our Lady of Light) Church, the one-story adobe with an orange- pastel roof and a steeple housing the original bell, still serves as a house of worship for local Catholics. On the first Saturday of every month, the Rev. Leo Ortiz of St.

Anthony parish celebrates Mass for the small faithful community of Canoncito. Many parishioners today are the descendants of the original builders of the church. Nuestra de la Luz was named after Luz Gurule, who donated the land for a church in 1881. Gurule would not live to see the church built, but her daughter Cruzita Gonzales, put her own IS children to work with other villagers to build the structure in the 1930s. "My mother and grandmother used to talk about it all the time," said 69-year-old Lupita Romero.

"We can do anything in this community with patience and willingness." Romero spent summers in Valencia with her grandmother in the family's stone house. She lives there today. Romero remembers how every month the women in the village gathered the church linens for starching and ironing for the next month's service. "The priest from Pecos would pick us up and take us to the church," Romero said. "So for his kindness, we offered to wash all the Luz Gurule, who donated the land for a church in 1881, would not live to see the church built, but her daughter Cruzita Gonzales put her own 15 children to work with other villagers to build the structure in the 1930s.

linens and get them ready for the Mass. Women had a big part in keeping up the church." At Nuestra de la Luz Church, from the church's beginning until now, women and girls worked to keep the church tidy. "There were no vigas in the church originally," Romero said. "Instead of painting the ceiling, we covered it with sheets of white canvas or cotton called cielos (skies) to keep dirt from seeping through the roof, into the church. The women worked so hard," she said.

"Once a year they took down the canvas, cleaned them by hand and starched and stretched them and put them back up. The men stayed out of it." Cieios were replaced by vigas about 25 years ago. Until her death in 1968 at the age of 106, Romero's grandmother watched over the church and parishioners like a hen with her chicks, Romero said. In the absence of an on-site priest, mayor- domos (caretakers) were appointed by the parish priest and entrusted the care of Nuestra de la Luz. Despite their best efforts, the aging church needed a major overhaul by 2000.

Vibrations from traffic on Interstate 25, which rushes by at speeds of 70 mph or more and is less than 500 feet away from the church facade, had caused severe cracking in the adobe structure. By recruiting the help of the Santa Fe- based Cornerstone Community Partnerships, an organization that works with rural communities in New Mexico to restore historic structures, the village was able to replace damaged adobe walls and build new ones. In 1996, the chapel was recognized as an historic landmark by the state Historic Preservation Office and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. The designation made the church eligible for funds to help with the renovations. Mark Lovato and his family, the current mayordomos, watch over the church and tend the cemetery grounds that surround the late Territorial-style church.

"There are gravesites under the church," Lovato said. "The cemetery was here long before the church. In fact, Luz Gurule, the woman who donated the land: Her remains are buried under the altar." The oldest graves date back to 1846. Many of the markers are hand-chiseled or possibly carved with a knife and written in Spanish. Some markers are faded beyond legibility while others are unmarked wooden crosses bleached by the sun.

Before the highway came through Canoncito in the 1960s, a family-owned general store, a corral and gas station served a community of about six families. Nora Varela's family was one of them. "There was always rain," she said. "Not like now. There used to be two big wells that served about six families.

I lived in a big house where the highway ramps are now." Varela remembers climbing the cottonwood trees around the church as a little girl. "The cottonwoods nearly killed me once, but also saved my life," she said. "I was a terrible kid. I was trying to learn how to smoke, so I climbed a huge tree next to the church to get away from my brother. But as I climbed up, the bark gave way and the branch snapped.

I fell and almost broke my head." But another tree in the village saved her life the day she fell into one of the village wells and almost drowned. "The well was full and suddenly caved in. I went clear down 8 feet." She said she escaped by scaling the jutting tree roots along the well's dirt walls. "Everybody used to get water from those wells, the Gurules, the Garcias and Moyas there were only five or six families. People would come and get water in barrels and bring them back home, but those days are long gone," Varela said.

"But we still have our church." Nora Varela and her husband Nick, both in their 70s, were chapel mayordomos for many years before retiring to their home behind the church. "We were always given donations by artists and construction companies outside the village," Nick Varela said. "Family, friends, even people not connected to the church. Everybody wanted to give to it." The article was first published in the Eldorado section of The New Mexican. Hands-on director leads Museum of Indian Arts and Culture Duane Anderson believes in keeping "an oar in the water" as director of the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture.

In truth, he seems to be pulling robustly on (at least) two oars at once. One is plunged into the current of cultural, archeological and anthropological research and writing. The other is guiding the museum in its mission of being a meeting ground of cultures presenting and interpreting the American Indian experience from the perspective of native peoples themselves and doing so in ways that are interesting and accessible to the general public. Anderson, 58, has been involved in similar kinds of activities for almost four decades. As an archeology student at the University of Colorado in Boulder, GUSSIE FAUNTLEROY he was part of a team that in 1963 excavated and reported on a skeleton, a discovery that fueled scientific and public debate about early North American peoples.

In the years since then he has written or co-written dozens of articles, papers, reports, books and chapters in other researchers' books on such topics as paleo-Indian burial sites and culture, American Indian pottery, archeological methodology, and repatriation. Most recently, Anderson coauthored a 22-page manuscript for an upcoming issue of American Public Works Antiquity magazine. He also has a new book in the writing stage and one under peer review. A third book, When Rain Gods Reigned, will be released in September by Museum of New Mexico Press. It traces the history of the clay rain gods of Tesuque Pueblo, the longest continuously practiced figurative art tradition in the Southwest.

All the time he's been busy with research and writing, Anderson has kept up his day jobs as well. In the late 1960s to early 1970s he served as director of the Sanford Museum and Planetarium in Cherokee, Iowa, the first museum in that state to be accredited by the American Association of Museums. He has been Iowa state archeologist; executive director of the Day- Ouane Anderson ton Society of Natural History in Dayton, Ohio; vice president of the School of American Research in Santa Fe and director of that institution's Indian Arts Research Center, along with serving on and holding leadership positions in numerous state and national professional associations. He's been MIAC director for the past two years. On his own time, Anderson creates inlaid stone jewelry and Spanish Colonial style pegged, not nailed) wooden furniture none of which is sold, but is given to friends or family.

But the accomplishment he is most pleased with at the moment is MIAC's 35 percent increase in attendance and more than 200 percent jump in revenues in the past few months at a time when most other museums are reporting a drop in attendance. The director attributes MIAC's success to a "hard-working and wonderful staff" and the opening of Milner Plaza, which gives the museum new public outdoor spaces, a performance circle and a recently opened restaurant. As project manager for the construction, Anderson exemplified his philosophy of museum leadership. "I don't mind painting a building or pushing rocks around," he says. "I'm a very hands-on director." you have news about a public employee, contact Fauntleroy at (S05) 988-4068, fax (505) 988-7262 or e-mail.

Get access to Newspapers.com

- The largest online newspaper archive

- 300+ newspapers from the 1700's - 2000's

- Millions of additional pages added every month

Publisher Extra® Newspapers

- Exclusive licensed content from premium publishers like the The Santa Fe New Mexican

- Archives through last month

- Continually updated

About The Santa Fe New Mexican Archive

- Pages Available:

- 1,490,360

- Years Available:

- 1849-2024