The Philadelphia Inquirer from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania • Page 21

- Publication:

- The Philadelphia Inquireri

- Location:

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Issue Date:

- Page:

- 21

Extracted Article Text (OCR)

Sunday, September 8, 1996 THE PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER A2I Nancy Anders showed Latin Americans how to operate sewing machines. Later, she realized she'd been 'training them to take our jobs." AMERICA: Who Stole the Dream? World War II, enabling millions of servicemen and women to attend college. It was the federal government that built the interstate highway system, linking towns, rural areas and cities. It was the federal government that initiated development of the computer, the machine that has transformed everyone's life. And it was the federal government that financed the technology and underwrote the early costs of the Internet, the global information superhighway that is projected to become a $79 billion-a-year business by the turn of the century.

America: Who Stole the Dream? The Inquirer, in a 1 0-part series, is writing in detail about American policies that are costing this country jobs. The series dates: Sunday, Sept. 8. Monday, Sept. 9.

Tuesday, Sept. 10. Wednesday, Sept. Thursday, Sept. 12.

Sunday, Sept. 15. Monday, Sept. 16. Tuesday, Sept.

17. Wednesday, Sept. 18. Sunday Sept. 22.

Another company moves offshore wages are counted in pennies eliminating American jobs. Because there's no middle ground, the progressive income tax designed so that the very rich would pay their appropriate share of the cost of ment has been gutted. And because there's no middle ground, the notion that government has a vital role in the economic direction of the country has been shoved aside. Either you believe in unfettered private enterprise, or you believe government should run the economy. Government always loses that argument.

But casting the issues so rigidly ignores what the federal government can dot and has done, to bolster the economic well-being of average Americans. Throughout much of this century, government played a critical role in the development of American society protecting the powerless, curbing the excesses of business, and creating a regulatory framework to safeguard the health and welfare of its citizens. Equally important, the federal government has assured opportunities, evened out the economic playing field, and tackled issues that neither Wall Street nor the market deemed significant. It was the federal government that spurred the greatest wave of home-building in American history after World War II with the Federal Housing Administration program to ensure mortgages for emerging middle-class families. It was the federal government that created the student aid program after 11 of which brings us full-circle to Marion, and the men and women who once worked for llar- wood Industries' and who lost their jobs, thanks to U.S.

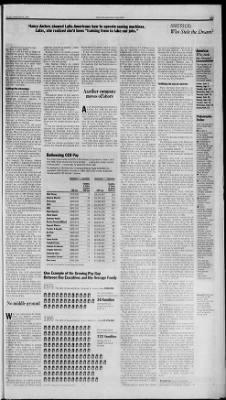

trade policies. Marion is in the heart of what Virginians call the Mounlain Empire, a region of lovely rolling hills, pleasant valleys and gentle streams. It is a place where jobs have never been plentiful. But small manufacturing facilities, especially clothing plants, have dotted the countryside along Interstate 81, providing jobs for area people, For more than half a century, Har-wood Industries, a maker of men's pajamas, robes and casual clothing, was Ballooning CEO Pay This chart shows what the CEOs of 20 selected corporations made in 1975 and 1995. It also shows how many families making the median income in those years it would take to equal the CEOs' pay.

For example, in 1975 the CEO of General Motors made $300,000, the equivalent of 22 families' incomes. In 1995, GM's CEO made $3,250,000, the equivalent of 82 families' incomes. Continued from preceding page less than he made before. Rude says AIG did what all large corporations are doing: "Big business today, if it can find a way to save a few bucks, they'll do it. The bean counters are running these companies anymore.

Anything they can do to make their quarterly projections, they do." As for the decision to replace its programmers, AIG issued a statement saying it had decided to assign the work "to outside contractors. In the company's judgment, the increasingly variable labor content of this work makes it impossible for AIG to efficiently staff this effort internally." Getting the advantage Not everyone at AIG has fared badly under the new economic rules. Some have profited handsomely from such bottom-line decisions: Maurice R. (Hank) Greenberg, for one. Greenberg, 71, is chairman and chief executive officer of AIG.

From an office near Wall Street, he presides over a business empire of 34,500 employees in more than 100 countries, with revenue of $25.9 billion in 1995 more than the gross domestic product of entire countries such as Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Panama or Uruguay. Greenberg is one of the 100 richest men in America, with a net worth estimated by Forbes magazine at $1 billion. He has a Manhattan apartment bordering Central Park and an ocean-front condominium on Key Largo in Florida. Since becoming head of AIG in 1969, he has earned a reputation as one of America's most abrasive, cocky and aggressive corporate executives. Once asked to sum up his business philosophy, Greenberg answered: "All I want in life is an unfair advantage." Among his advantages has, been instant access in Washington.

For example, the company lobbied for and won a special provision in the Tax Reform Act of 1986 exempting certain of its operations from a crackdown on foreign tax shelters. If you pick up a copy of the Internal Revenue Code, you can read the custom-tailored tax law written for AIG. It states, in part, that this section of the new tax law will apply to everyone except "any controlled foreign corporation which on August 16, 1986, was a member of an affiliated group (as in section 1504(a) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 without regard to subsection (b)(3) thereof, which had as its common parent a corporation incorporated in Delaware on July 9, 1967, with executive offices in New York, New York AIG was incorporated in Delaware on July 9, 1967, and has its executive offices in New York. That little provision and a similarly arcane clause written for another big insurer Cigna were worth an estimated S20 million to the two companies. They would have been obliged to pay that much in taxes had not a friendly, but anonymous, member of Congress' tax-wriling committees inserted that exemption into law.

In any event, 1986 was not the first time that AIG helped write the tax laws. In 1976, the company was the prime beneficiary of a section in the Tax Reform Act that exempted AIG and other large insurers from taxes on some of their offshore operations, saving them millions of dollars. In the wake of AIG's replacing its U.S. computer programmers, 1995 proved an especially good year for Greenberg. His salary and bonus totaled $4.15 million.

That worked out to $80,000 a week, or more than the average AIG programmer earned in a year. Greenberg also held unexercised stock options valued at $23.6 million and owned 10.7 million shares of AIG stock worth $1 billion or so. Let's review: In 1995 Jim Rude, a certified member of America's solid middle class, saw his earnings fall 42 percent. Maurice Greenberg saw his AIG stock more than double in value, as he solidified his membership in America's Top 1 Percent Club. Philadelphia Online Visit The Inquirer's World Wide Web site to: Access a summary version of the series, some of its photos and graphics Subscribe to Philadelphia Online ($6.95, call 1-800-811-3139) for a full-length version.

Plus, more info and graphics, games, a searchable database, online discussion with the authors, and the earlier series, America: What Went Wrong? Test your knowledge of the U.S. economy Try your hand at decisions faced by our government and corporations. Then, check officials' choices and their consequences Share your opinions in readers' online forums Link to important related World Wide Web resources. Learn about trade and immigration policies, see latest national layoff announcements, address your concerns to officials, contact companies you read about in this series, join in a survey on free and fair trade (are you willing to pay more for jeans made in the even -order a Robber Baron game and build your virtual fortune. For more on America: Who Stole the bookmark your browser: Philadelphia Online phillynews.com was hard on employees, but he felt it was the right decision not just for Harwood but for the nation as a whole.

"As much as this has hurt my industry, it is my belief and feeling that our government is going about this in the correct manner," Watkins said. "I think that they have to write the industry off and go for high-tech and let the less-expensive labor countries produce the apparel and other things. "I know it has hurt a lot of people, but it is also helping a lot of people in the long run, the consumers." Fulfilling the social contract When Harwood shut Marion, the company ceased to manufacture in the United States. The gradual move of its plants offshore was complete two to Honduras, one to Costa Rica. For many American apparel-makers, Honduras has become the country of choice in recent years.

The Central American nation of 5.3 million people has been highly successful in attracting U.S. plants because of cheap labor, no taxes and a solicitous government. American companies that manufacture products there in specially created export zones are exempt from all import and export duties, from currency charges when they ship profits back to the United States, and from all Ilon-duran taxes a "Permanent Tax Holiday," as the Honduran government describes it. Best of all, they are exempt from U.S.-style wages. The minimum wage of the Honduran factory worker, according to that government's statistics, is 48 cents an hour, including benefits or about S25 a week in take-home pay.

Even by Latin American standards, that's low. Mexicans who work in American plants on the border now earn, on average, $60 a week three times the average pay of Hondurans. And Mexican wages, of course, are only a fraction of the $7 to $8 an hour that a U.S. worker would be paid. For all the talk about the need to be "competitive," there is no way a plant in the United States paying minimum wages and no benefits could compete with a Honduran plant where the pay is 48 cents an hour and where profits are exempt from taxes.

Not surprisingly, many American companies have moved some operations to Honduras in recent years. The list includes such familiar names as Sara Lee, Bestform, U.S. Shoe, Fruit of the Loom, fend Wrangler. One of those, Sara Lee, announced plans in the summer of 1996 to acquire Harwood. Harwood was one of the first to capitalize on Honduran incentives; its first plant was built there in 1980.

Having successfully transferred all of Harwood's operations abroad, Michael Rothbaum, who then was the company's chief executive officer, subsequently offered some words of advice to American manufacturers who might be considering a Caribbean operation. After first warning that the process was not easy think of it "as if you were starting a plant on the moon," he wrote in a trade journal he then assured them it was worth it. If "approached correctly, the savings in labor costs can be significant." Rothbaum went on to paint a picture of the average worker: "Caribbean employees work longer hours, from 44 to 48 per week, and they travel further to work, sometimes two hours by bus each way. Some also attend school at night. For many, the only decent meal they get each day is the one served in your cafeteria.

Also remember that Caribbean employees are younger than your domestic workforce. The average age in a Caribbean plant may be 19 to 20. "Medical care as we know it is not available, and people come to work when they're sick because that is where they may find a doctor or nurse. To a great extent, you, the employer, must compensate for these differences in conditions through the social contract you make with your employees in order to achieve acceptable performance." If Rothbaum believes U.S. employers must enter into a social contract with their Caribbean 'employees, it.

is just such a contract that their abandoned employees in the Uniled States believe has been broken by culling off jobs, wiping out benefits, lowering their standard of living. And the outlook for a long-term social contract in countries such as Honduras isn't good, either, if history is any guide. Harwood's first offshore plant was in Puerto Rico. When wage rates rose there, the company moved its apparel production to a lower-wage country, Nicaragua. But alter political upheaval there in the late 1970s, Harwood relocated to Honduras and Costa Rica.

One longtime Harwood employee at Marion, Carney Powers, after noticing how the company kept moving from one developing country to the next to cut costs, said he once asked a Harwood manager if there was any chance, as wages rose in developing countries, that Harwood might, shift some of its manufacturing back to the States. No way, the manager told him. "There's too many countries out there." one of the fixtures of the Marion economy. It employed several hundred seamstresses, cutters, warehousemen, packers, mechanics and office workers. By national standards, the pay was never good.

In 1992, the average for women in the sewing department was $6,75 an hour, roughly $14,000 a year. But Harwood did have a health plan, the women were close to family and friends, and it provided steady work. Until Aug. 31, 1992. That day, Harwood announced it was closing the sewing operation, eliminating 120 jobs.

In a statement all too familiar to American workers, officials said they regretted the decision but that it was "necessary because we were not competitive on most products." The company said it planned to keep open a distribution center and office; but they, too, were phased out over the next 18 months. For years, Harwood had been shuttering plants in the United States and, under pressure from retailers to cut costs, shifting production offshore first to Puerto Rico, then Nicaragua, and finally to Honduras and Costa Rica. The Marion employees had watched as the company closed other plants. They knew the signs did not look good. Yet the layoff still came as a shock.

"It. does something to your self-esteem," said Ann Williams, who closed out her 20 years at Harwood working in the office. "You don't get over it. I don't know anyone who has really gotten over it. We all knew we hadn't been singled out.

Everybody had been let go. But you still take it personally." For Darlene Speer, the shutdown hurt, both personally and financially. "I loved my job, but after the way they treated us al the end, I was almost glad to get out of there," she said. "We all worked so hard. They didn't close it because of our work." Speer, who is divorced and the mother of two grown children, ulti-.

mately wound up with two jobs, with a furniture maker and a video store. Together, she said, the two equal roughly what she earned annually at Harwood. "But you can't look back," she said. "I've gone ahead with my life. And, for the most part, I'm happy.

But I'll tell you, it's hard to start over." Nancy Anders, who worked in the sewing department for 25 years, recalled how she'd felt such a sense of responsibility toward the job. She went to work regardless "when I was sick, when my family was sick," she said. At the company's request, she even went to Nicaragua in the late 1970s to help train new employees at a plant Harwood had built there. Anders spent six weeks showing Nic-araguan women how to operate sewing machines. At the time, she didn't think much about it.

She felt sorry for the people, who were so poor. It was only years later, reflecting on the trip, that she realized she'd been "training them to take our jobs but didn't know it." "I was bitter at first," she said of the closing. "But the more I thought about it, I thought, 'If they don't want me, then I can find a job Eventually, Anders did find one. "1 have a good job now," she "It's a part-time job. I'm Wal-Mart's peo-ple-greeter, and 1 love it.

And I think I'm the best people-greeter Wal-Mart's got." Smiling and upbeat, Nancy Anders has gone on with her life, even though she earns less and must pay for health coverage. Yet for her, the greatest loss can't be measured in dollars and cents. Ilar-wood's closing cheated her out of a chapter of her life. For 25 years, she'd gone to festive dinners hosted by employees when workers retired. On these occasions, employees chipped in to buy the retiree a finely crafted oak rocking chair made at a nearby furniture factory.

It was a lasting gesture of affection from those who stayed to those who were departing, and the rocking chair came to symbolize not only a life of leisure but also a kind of closure to a life of working at the Harwood plant. "I went to the retirement dinners for 25 years and I couldn't wait to retire so I could get one of those great big rocking chairs," she said. "1 just dreamed about that day. That was my goal, getting that rocking chair." When Harwood announced the closing, Anders knew there would be no retirement dinner, no rocking chair. "I went home that night and I cried," she said.

"My husband thought I was crazy being so upset over a rocking chair. He said, get I could have bought the rocking chair. But it wouldn't have meant the same after all those years. I missed getting that rocking chair almost as much as I hated to lose my job." Wendell Watkins, a Harwood vice-president and the last manager of the Marion plant, said the company regretted the closing but had no choice. "We have always manufactured private-label goods I for department stores! who can shop the world and get the best price they can," he said.

"Now, that's great for the U.S. consumer and they are the real beneficiaries. Our major customers always insist on having the lowest price. They tell us, 'We'll bring it in from the Orient if you can'1 do something to match the "I think we did a great job of keeping it open as long as we did but we just could not compete with the competition we had to meet and pay U.S. labor prices." Waskins said he knew the closing I "TIT'''" -r-rr-.

Families Families it takes it takes to equal to equal CEO pay CEO pay CEO pay CEO pay Walt Disney $122,668 9 $8,018,807 203 General Electric $500,000 36 $5,250,000 133 Coca Cola $293,225 21 $4,880,000 124 TRW $341,200 25 HsTs'iTT" 122 IBM $537,532 39 $4J75fi00 12? Bank America $348.018 25 $4,541,666 U5 Allied Signal $450,000 33 $4,350,000 110 Eastman Kodak $386,286 28 $4,282,496 108 Archer-Daniels-Midland $247,916 18 $3,612,171 General Motors $300,000 22 $3,250,000 82 Procter Gamble $458,333 33 $3,233,000 82 Du Pont $248,436 18 $2,700,000 68 $443,900 32 $2,677,400 68 Union Pacific $382,600 28 $2,560,000 65 Campbell Soup $299,167 22 $2,204,917 56 Johnson Johnson $325,000 24 $2,140,931 54 Colgate-Palmolive $290,386 21 $1 ,984667 50 Kimberly-Clark $200,833 15 42 Caterpillar Tractor $261 ,667 19 $1,564,000 40 Dow Jones $187,000 14 $1,125,000 28 SOURCE: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission One Example of the Growing Pay Gap Between Top Executives and the Average Family JL tf I The CEO ot General Electric, Reginald H. Jones, made $500,000. 2. SL .12.

Ao HiQ rnmnencatinn in ji in ai a a Op On nO 0 On On On On On On On On On in ji in fi fi ifi ifl Hli in in ii equaled the income of 36 families earning the U.S. median income of $13,719. No middle ground Research help was provided by Bill Allison. Also contributing to the research were John Brumfield, Harold Brubaker, Tirdad Derakhshani and the Inquirer library staff. fhat has complicated Ihe debate about the nation's economic course is that most policy issues viJO The CEO of General Electric, John F.

Welch made $5,250,000 a in in in in On On On On On. On On On On On nnnnnjiJifiii'ruiJi His compensation equaled the income of in fi in fi in fi fi ji i in fi fi fifififitffififififififi On Oq On On Co in in in in in in are cast in eitheror terms. Either you're for free trade, or a protectionist. Eil her we should throw open the doors to immigrants, or keep out' foreigners. Either you want government off business' back, or you favor shackling American companies with onerous regulations.

Either you're for lowering taxes, or you're for soaking the rich. Absent from the debate is serious talk about the need for a middle ground for a balance between the interests of corporations and of employees, between unrestricted trade and controlled trade, between preserving the nalion's historic tolerance of immigrants and protecting American workers from a glut in the labor force. And there is a middle ground just as there is for all human behavior. Yet for their own reasons, partisans cast these issues as eitheror, and they're portrayed that way in the media. Because there's no middle ground, the doors have been flung open to imports often made by workers whose in in in in fiflfffiflfiflflfififlflfiftflii Op On On, On On On On O-i On Op, On ininnmumirtinininininin On On On On On On on On i On On on On Tomorrow: How U.S.

policies enrich multinational corporations at lithe expense of American workers. SOURCA: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Get access to Newspapers.com

- The largest online newspaper archive

- 300+ newspapers from the 1700's - 2000's

- Millions of additional pages added every month

Publisher Extra® Newspapers

- Exclusive licensed content from premium publishers like the The Philadelphia Inquirer

- Archives through last month

- Continually updated

About The Philadelphia Inquirer Archive

- Pages Available:

- 3,846,195

- Years Available:

- 1789-2024