Democrat and Chronicle from Rochester, New York • Page 11

- Publication:

- Democrat and Chroniclei

- Location:

- Rochester, New York

- Issue Date:

- Page:

- 11

Extracted Article Text (OCR)

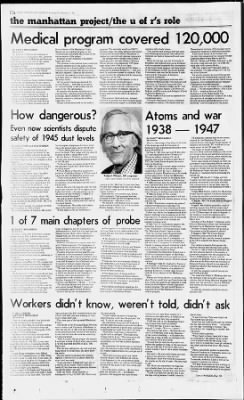

1 2 A SUNDAY DEMOCRAT AND CHRONICLE. KaheMpr. February 15, 1981 the masuSuatoim it's irle Medica ere'd cov progra radiation did to body tissues. They learned that uranium dust can cause acute kidney poisoning and that radioactive materials can destroy human cells and cause cancer. When the war was over, the University of Rochester was credited with having developed such occupational standards that no employee of the atomic bomb program had been injured in the workplace.

In 1947 the Atomic Energy Commission took over the Manhattan Project work, and the University of Rochester continued its research. Much of the experimental work was later published by McGraw-Hill: Pharmacology and Toxicology of Uranium Compounds (four volumes by Dr. Harold C. Hodge and Dr. Carl Voegtlin), Biological Studies with Polonium, Radium, and Plutonium, and Biological Effects of External Radiation.

Those studies still are used as standards for occupational safety. During the Manhattan Project, a shipment of radioactive sodium to Rochester from the By NANCY MONAGHAN D4C Stall Writer Dr. Stafford L. Warren was chairman of the Department of Radiology at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry when he was appointed chief of the medical section of the government's top-secret Manhattan Project. It was April 1943, and the Allies had seized strategic points in Tunisia.

In the United States, the atomic bomb was being developed. And one of its chief components was high-purity uranium. The War Department began intensive mining efforts after the Manhattan Project began in 1942 and chose chemical plants for processing the ore. But little was known about the health hazards to the scientists and factory workers who would be handling the compounds. Radium, a highly-radioactive element of uranium, was blamed for the World War I deaths of those who painted the luminous substance on watch dials and other devices.

At the request of Major General Leslie R. Atoms and war dangerous! Even now scientists dispute safety of 1945 dust levels Grove, director of the Manhattan Project, Warren set up a medical program for the 120,000 people nationwide who worked on the various aspects of the project. Scientists at the University of Rochester began their work. Ten divisions in the medical school conducted scientific experiments so the medical team could advise the industrial plants with defense contracts how to protect their workers from radiation exposure. Others at the university continued the research on atomic energy, that had begun there in 1938, for the development of the atomic bomb.

All the project '8 work was classified. No one but Warren and later his successor, Dr. Andrew Dowdy was to know the full scope of the URs participation. In separate laboratories, the divisions of pharmacology, radiology, genetics, hematology, pathology, spectrochemistry, instruments, statistics, veterinary, and special problems began their work. Animal colonies were bred for the medical blood samples of employees for heavy metal during the project years, and is retired, said: "There's always that kind of controversy about the levels.

They change with the times. It depends on who is saying what's safe." John Hursh of Pittsford, a retired radiation biologist who worked on the Manhattan project at the UR, said: "So far as I know, no injuries resulted from the exposure. I really don't think there was anything remiss." David Maille of Henrietta, an associate professor of radiation biology at UR who wasn't connected with the Manhattan project, said: "There would probably have been an atmosphere of dust at those levels (500 micrograms). You could almost see the stuff, I would guess." Wilson, the only UR scientist to see the state report that criticizes the UR for approving the higher dust levels he was given a copy by the Democrat and Chronicle called it "a severely slanted document." He said he doesn't belittle the danger of radiation, but said uranium dust isn't one of the major hazards. "It disturbs me.

They make such a heavy play on the radiological implication." Wilson said so little was known about Corps of Engineers and the General Services Administration in New York City, and from the Niagara County Clerk's office, the city of Niagara Falls, and the state departments of environmental conservation, health and transportation. Freedom of Information requests were filed with 12 federal agencies. The Department of Energy alone reviewed more than 600 boxes of documents and turned over 67,588 pages. Fourteen witnesses testified when the state Committee on Environmental Conservation held a two-day public hearing in Buffalo, which produced 522 pages of sworn testimony that the Army had dumped at Love Canal and about the nature of military-related chemical production, storage and disposal in the region. The task force compiled a two-volume report, broken down into seven primary chapters, one of which was devoted to the University of Rochester, and it was presented by the assemblymen on the committee Maurice Hinchey, Alexander B.

Grannis, Joseph T. Pillittere, and Matthew J. Murphy to Fink, The principal authors from the task force were special counsel Michael P. Zweig and environmental analyst Gordon M. Boyd.

Some of the report's recommendations: By JACK JONES and BILL O'BRIEN DC Stall Writers Scientists agree that exposure levels at uranium processing plants permitted by two University of Rochester scientists during the top secret Manhattan atom bomb project could have been dangerous, but they disagree on how dangerous. Dr. Harold C. Hodge, now in California, who provided medical justification in 1945 for increasing the levels of uranium dust in the atom bomb plants, said: "Based on what I know today, I wouldn't recommend the 500 microgram level." Hodge and another scientist, Carl Voegtlin, approved raising the level of uranium dust to which factory workers were exposed from 150 then believed to be the safe level to a maximum of 500 micrograms per cubic meter of air. They and the War Department said it was to spur production of the atomic bomb during World War 11.

Robert Wilson of Pittsford, who is UR's environmental health and safety officer and was an engineer at the project from 1944 to its completion, said: "There wasn't enough of a uranium problem there to amount to a hill of beans." Luville Steadman of Brighton, who tested Massachusetts Institute of Technology was to suspend air shipment of radioactive materials. Little is now known of the incident, but the pilot who transported the container became suspicious when he saw Warren and Drs. Harold C. Hodge and William Bale pick up the box with a long pole and put it on a flat-bed truck piled with concrete blocks. A "My God.

what's that?" the pilot called to the scientists. "I've been sitting over it all the way from Syracuse." For security reasons, he received no answer; so, he traced the shipment and reported to his supervisor. It was several months before federal regulations were established and air transport of radioactive materials resumed. Shortly after the war nded, Grove published a book The Manhattan Project: Now It Can Be Told revealing the story of the development of the atomic bomb. The University of Rochester isn't listed in the index, but a portion of one page in the text is devoted to a brief, general discussion of the university's medical program for the project.

1947 UR physicists continue their atomic energy research for the Manhattan Project, and medical doctors research the health hazards of radiation and uranium. The workforce on the secret project at the UR totals 350. The project is housed in long, squat, two-story brick cyclotron building at the corner of Crittenden Boulevard and Elmwood Avenue behind Mt. Hope Cemetery, where radiobiology and microwave research pontinues today. Safety experiments are stepped up when the government begins importing African uranium ore, which was more radioactive than the ore mined in Colorado that had been processed in the Manhattan Project factories.

Linde Air Products in Tonawanda begins processing the African ore. April 1945: Harold C. Hodge and Carl Voegtlin, the chief toxicologists in the medical program, recommend a maximum allowable lunl AAnfiAnlntin tlta dip (won rimao tliA uuut ciincuti anuii in mc an iviiiw tuues nn; accepted safe level in the Manhattan Project's uranium plants. June 1945: Warren notifies the Manhattan Project district engineer to increase production by using the new dust concentration levels Hodge and Voegtlin have recommended. August 1945: The atomic bomb is dropped on Hiroshima.

April 1946: Stafford assembles a staff of radiology experts from UR for atomic bomb testing in the Bikini Atoll. A camera developed by the UR department of optics is shipped to the Pacific to record the explosion and is erected on Amen Island, eight miles from the Bikini Atoll. Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson sends Grove to Rochester to honor the University of Rochester for its Manhattan Project work. President Truman describes the project as "the greatest scientific gamble in history." January 1947: The Atomic Energy Commission picks up the work of the Manhattan Project, and the research program at the UR is renamed the Atomic Energy Project.

Two radiation lawsuits filed against the university shortly after the war were settled. On Jan. 9, 1946, in what was believed to be the first radiation lawsuit in the country, a government engineer who was assigned to the UR for the Manhattan Project sued the university for $200,000. Arthur Cardinal, whose office was on the floor above the cyclotron on Elmwood Avenue, claimed he was exposed to dangerous radiation that damaged his white blood corpuscles. In 1947 the university settled the 8uit and paid Cardinal $4,500.

Two years later Ralph K. Moldrum, who was the caretaker of the university's animal colonies, died at Strong Memorial Hospital. His widow sued the university, claiming Moldrum died because he was exposed to radioactive materials. In 1952 the university settled the lawsuit, paying $1,750. look at them.

"It was horrifying. They were bright red. They didn't have any hair." Sometimes she could see through the window into the next laboratory where technicians give the dog9 "something to breathe." She learned later the "something to breathe" was radioactive. Nobody asked questions. "When I went in there, I was told to keep my mouth shut." She didn't tell her mother or her husband what she was doing.

"I do know before I worked there some girl evidently had talked and was fired for it," Mrs. Booth said. Others, particularly workers in plants like Linde Air Products in Tonawanda, knew even less about what they were doing. Mary Lyons, of Riverview Boulevard in Tonawanda, worked at Linde in 1944 at the company's uranium ore refinery. "We didn't know what we were wnrkino nn But you have to understand the timoa hoH a brother and friends who were in the service overseas.

program. The university would use 299,575 monkeys, dogs, rats, mice, hamsters and rabbits to study the biological effects of exposure to radioactive materials and uranium compounds. The carcasses were trucked to the Project's burial ground at the Lake Ontario Ordnance Works, the site of an abandoned TNT plant eight miles north of the Love Canal. Researchers examined special film badges developed by Eastman Kodak Co. that were worn by employees exposed to radiation.

They could calculate the radiation level by examining the reaction on the film. They mixed and tested elements to find a laundry detergent that would remove radioactive residue from the workers' clothing. They developed electronic instruments to measure the amount of radiation exposure in factories, tested uranium compounds for their toxicity and studied the effects of radiation on skin. They analyzed blood and urine, designed and built instruments for their testing programs and examined animal organs to determine what j. i in iwutjrr vvuson, ui engineer calls state report 'severely slanted' uranium in the 1940s that "it must have been by some kind of magic that these guys (Hodge and Voegtlin) came up with some pretty reliable numbers." Tests were run over several years, Wilson said, on animals.

Their exposure level was increased 10 times the 500 microgram level to 5 milligrams per cubic meter of air. "We raised it to the highest level we could, using uranium dioxide, and (it did) not show kidney damage," Wilson said. Turn to SCIENTISTS, Page 19A of probe New legislation for additional federal funds for Love Canal and for health studies of the people who may have been contaminated at Love Canal; The Department of Defense would reopen its investigation into military involvement in the contamination of Love Canal. The Departments of Energy and Defense and the Environmental Protection Agency should study the disposal of radioactively contaminated chemical wastes in underground wells on the property of Linde Air Products in Tonawanda; State and local environmental officials in the states that housed former Department of Energy, Atomic Energy Commission and Manhattan Project facilities should examine the history of those operations; The Department of Energy and the Department of Health and Human Services should determine the health effects of excessive radiation exposure of workers at government facilities in the Niagara region; The federal government should pay for health studies of exposed to excessive uranium dust during the Manhattan Project. the news reports.

"I didn't realize the extent of what, that damn thing was until I saw the pictures," she said. "It just hit me in the stomach." She read about the project she worked for and that safety precautions prevented accidents among the thousands of people who contributed to developing the bomb. She said it isn't true. "Blood tests would come in through the regular mail in packages." They came from Chicago and St. Louis.

"They were put in the centrifuge with the idea you would tell immediately just how bad a person had been affected." She remembers five severe cases in the blood vials. One was from a man whose experiment at Los Alamos exploded before he could get out of a room. "There were no names given, but I knew because the girl I was working with told me it had happened to the young scientist down in Los Alamos. When we took the blood sample, we knew he was going to die," Mrs. Booth said.

He did. Two of her three children the two born after she worked at UR have health problems. Her daughter had cysts on both ill it: JF of 7 main chapters 1938 By NANCY MONAGHAN Staff Writer Here is a chronology of key dates in the birth of the atomic age and the University of Rochester's role in developing the atomic bomb during World War II. On Aug. 6, 1945, five years and 92 days after a 27-year-old scientist at the University of Minnesota isolated uranium-235, which explodes with a force 30 million times that of TNT, the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

1938: The world's second largest cyclotron commonly called an atom smasher is completed at UR by Dr. Lee A. DuBridge, professor of physics. Experiments on the atomic nucleus begin. Later, during the Manhattan Project, DuBridge worked on developing radar at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

1939: Germany bans the export of uranium from Czechoslovakia, which has one of the world's few known deposits of the element. Physicists believe the embargo means but one thing: Germany is working on an atom bomb. 1940: Dr. Alfred O. Nier isolates Uranium-235.

DuBridge speculates it will take 20 years to develop the isolation process for any practical use. 1941: UR scientists complete two years of research with radioactive materials. The government calls on those scientists and others throughout the country for secret defense work. Fifteen days before the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor, DuBridge tells an audience at the City Club that 65 to 75 percent of all U.S. physicists and nearly 50 percent of all chemists are engaged in defense work.

1942: The U.S. Government organizes the Manhattan Engineer District of the Army Corps of Engineers to develop an atomic bomb. The "Manhattan Project" begins in June. Over the next four years the government would spend $2 billion for 1,200 defense contracts with more than 25 universities a major group is at the University of Chicago and more than 37 companies in 19 states and Canada. A weapons research laboratory is built at Los Alamos, N.M., and is now one of the country's leading nuclear facilities.

In September the Manhattan Project buys a industrial complex in Oak Ridge, where 45,000 employees would engage in fissionable uranium-235 from natural uranium. February 1943: Dr. Stafford L. Warren of the University of Rochester is invited to lunch by Dr. Albert K.

Chapman, vice president of Eastman Kodak to meet Major General Leslie R. Grove, director of the Manhattan Project. Warren and Grove adjourn to a private room, where Warren would later say Grove locked the door, closed the transom and inspected a closet before he asked Warren to head a top-secret medical program. The next month Warren is appointed chief of the Manhattan Project's medical program. ovaries; her son, open heart surgery for a stricture on the main artery, a condition the surgeon said may have been congenital.

Could her work on the Manhattan Project have caused those health problems? "I think like that. I know I have been exposed. I thought, 'What can I One aspect of her work the days she was sent to a windowless room in the basement of the cyclotron building still puzzles her. There was a chair, a table, an instrument she can't identify and a stop watch. "I would have to press the stop watch and register the number of clicks on the instrument.

I was just told that if the clicks went over a certain number, I was to call a special telephone number. She went to the room eight times, and took a book or her knitting to pass the hour. She doesn't know who would have answered the number on the slip of paper. She never had to call. Mrs.

Booth also remembers the dogs that were wheeled down the corridor, each in a separate container. Usually they were beagles. "I used to go back into the lab when I saw the dogs coming because I couldn't stand to By NANCY MONAGHAN D1C Stall Writer On June 1, 1979, New York State Assembly Speaker Stanley Fink ordered a legislative inquiry into the toxic contamination of Love Canal in Niagara Falls. As the task force collected documents, one puzzling question remained: The documents revealed that the Army Ordnance Department, the Chemical Warfare Service and the Manhattan Project were all involved in chemical production and uranium processing in the region. A preliminary report of the Assembly's investigation, issued May 29, 1980, charged that the federal government improperly disposed of chemical wastes from those projects and had not adequately decontaminated the Love Canal region.

The Department of Defense again denied that the Army had a program to dump wastes into Love Canal and other areas in that region. The task force widened its investigation. For four months the task force gathered documents from the National Archives and the Center for Military History in Washington, the National Federal Records Center and the Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland, the Army orkers By BILL O'BRIEN and NANCY MONAGHAN Stall Writers When the bomb exploded, June Booth felt like she had been hit in the stomach. She finally knew what she had been working on at the University of Rochester when the atomic bomb was tested in Alamogordo, N.M., on July 16, 1945, her birthday. She remembered the bright red dogs with no hair that she had seen through the window in one of the university's labs.

For six months in 1944 Mary Lyons came home from her job at a Tonawanda refinery, her hair stiff with a dust that wouldn't come out. She still doesn't know if it was uranium dust. Donald Evans remembers stern, federal guards at the Tonawanda plant in 1944. When he went to work 11 years later in that plant, he was warned about the dust still clinging to the beams and rafters of the wooden shell of the building that had been the uranium refining plant where Mary Lyons worked. Many workers in Rochester and Tonawanda didn't know they were part of the rush to make the atomic bomb in the mid-1940s.

They have didn't know, weren't told, didn't ask vague pictures that don't connect because they weren't told what they were working on. And most of them didn't ask. They were part of the top-secret Manhattan Project. June Booth of 130 Woodland Road, Pittsfordj went to work at the University of Rochester in 1944, and she left in 1946: She was a technician in the spectrochemistry division of the medical school, and she knew the work was, something for the government. "What I actually did was prepare the samples.

I would get a bottle of liquid which was actually a rat that had been dissolved in acid," Mrs. Booth said. The rats were radioactive, she said, and were being tested for lethal doses. She never knew the results. She also tested blood taken from workers exposed to radioactivity at plants where the atom bomb was made.

"I was told that if I happened to get any of it (blood) on my hands, I was to wash my hands off, but there was no protection between me and the bottle," she said. After the Trinity Bomb exploded at Alamagordo on July 16, 1945, Mrs. Booth read Turn to WORKERS, Page 19A.

Get access to Newspapers.com

- The largest online newspaper archive

- 300+ newspapers from the 1700's - 2000's

- Millions of additional pages added every month

Publisher Extra® Newspapers

- Exclusive licensed content from premium publishers like the Democrat and Chronicle

- Archives through last month

- Continually updated

About Democrat and Chronicle Archive

- Pages Available:

- 2,656,601

- Years Available:

- 1871-2024