The Republic from Columbus, Indiana • Page 6

- Publication:

- The Republici

- Location:

- Columbus, Indiana

- Issue Date:

- Page:

- 6

Extracted Article Text (OCR)

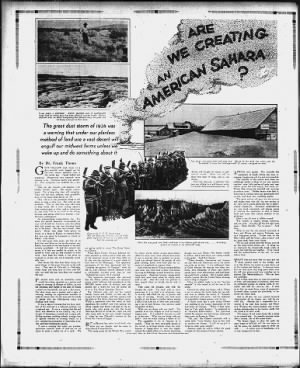

L-iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiniiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiH' czininfiiiiiiiiiii iziiiTOniiinnrtmnmmiininiiiiiiiHiifiiiiiiiHiiiiiiiiiunnnTi rfC-f1-; 'f "-rf -4- S- IS 1 Crau maka a differenoe! Above: specimen range land on "which grass has been allowed adjacent area, on vthich overgrazing has skinned let heavy rains get in their I The great dust storm of 1934 was awarning that under our planless method of land use engulf our midwest wake up and do something about it v.v1 Blown fcjj the wind into dunes over the and, of course, can grow no corn. A FRICA also speaks. For centuries' th population of South Africa has been increasing, though even yet it is not over-crowded. The methods of the natives have been astonishingly similar to those of our own western ranchers raise little patches of grain and vegetables, graze the land empty and move on. Winds whip across the denuded soil, scouring its surface away.

Sudden heavy raini lash it, furrowing it, cutting cattle and game-paths into runnels, and these into crumbling gullies. The good surface soil goes into the, streams and chokes them with silt; the new surface is not only cut to pieces physically but is impoverished chemically. European administrators are very much concerned, and discuss means of inducing the population to shift to better lands and cease their ruinous methods df exploitation. Does it not all have a familiar sound? The remedy is simple though laborious, and not Just this: fill the soil with roots again. Quite literally, "Go to grass 1" And trees.

What is now the rich plowed corn-land of Iowa and Illinois and eastern Nebraska was once long-grass prairie. Farther east, in the Ohio valley and the Great Lakes country and the deep south, there were forests. We cut and burned down the forests, plowed out the deep-rooted prairie sod. In doing so, we destroyed the innumerable tough cords of roots, that held the soil together. If we would end the insubordination of the soil, we must restore them.

does not mean that we must give the whole country back to the forests, and wait, like Elijah, for ravens to come down out of the treetops and feed us. It does not mean that we must grow only long grass where now the tall corn grows and turn ourselves out to pasture, like Nebuchadnezzar. We can keep our cornfields. But it does mean that we must set regiments of trees, and phalanxes of stubborn, deep-rooted permanent grasses on sloping lands, to discipline and' halt the runaway soil. It does mean that we must throw zones of permanently-rooted plants around the plowlands, to imprison the truant land.

And alL this, the cow. patient bereaved foster-mother of our human race, will be our chief ally. Already she. is responsible for quarter of the total farm income; and Secretary Wallace, the farmer-scientist who is now adding statesmanship to bis laurels, insists that she needs a lot more work. The menace of soil waste looms like a genne in an oriental tale.

Its possible exorcism reads like a nursery tale of the sunset lands: The fanner began to plant the seed, the grass began to hold the soil, the cow began to eat the grass, the children began to drink the milk. A whole cycle of beneficence, if it is only inaugurated in time. t' Mk. 5Lt. i ixr Once iiis Bas gooJ corn onf and now it picture of erosion in for wheat, wheat, wheat, always more wheat; called for meat, meat, meat, always more meat.

It was a patriotic duty to produce in excess. Land was plowed beyond the margin of safe grain farming, herds were bred past the capacity of rangelands to support them. And when the men of Europe stopped killing each other and went back to their own farms, throwing tariff hedges around themselves, down came prices. American farmers, unorganized, could only meet lower prices by raising more stuff to sell. And the land was plowed to dust, grazed clean as though shaved with a razor.

Then came the drought, and with the drought the wind. The land, with no more grass-roots in it to hold it in subjection, rose in anarchy and filled the sky, a portent and a sign of warning. Peopie who had never, thought of the farmer's troubles before, wiping a film of his farm out of their eyes and coughing it out of their throats, were perforce made thoughtful of them. What are we doing with our land? The question is on city tongues as well as country tongues now. It is asked in the east as well as in the west- What are we doing with our land? Are we really making a desert of it? The suggestion is not as fantastic as it sounds.

There are other man-made deserts in the world, or at least deserts where the recklessness or hunger-drive of men has supplemented the unkind offices of a slowly dessicating 1 i miiii i i rrnni ilinntwiimiii i i 9 r1 rAWT" ii jiy 7 work' a vast desert wi farms unless we jr te C. C. C. ores? nrmy. We can ecp our cornfields, but rce must plant regiments of trees to clifciplme and halt the runaway soil.

are getting ready to create The Great American Desert. When Brain-Truster Thomas Jefferson became president a century and a third ago, one of the important moves in the New Deal of his day was the purchase of a great chunk of land west of the Mississippi. The opposition newspapers of his time denounced him for "usurping the powers of Congress" when he did so, and Jefferson himself admitted (with a red-headed, freckled grin) that he had "stretched his power till it cracked." The opposition newspapers also declaied that the fifteen million dollars of taxpayers' money which Jefferson had squandered on this 800,000 square miles qf territory was just poured into a hole for was almost all of it in The Great American Desert? But Jefferson only sent out his trusted friends, Lewis and Clarke, to look over the bargain he had bought, and they quickly laid the ghost of The Great American Desert myth. Within a generation after the return of their expedition, the scoffers sons were getting rich selling wagons and plows and guns to the pioneers who were going out into this Great American Desert, to break the virgin sod and raise crops such as not even Joseph dreamed of when he was Pharaoh's overseer in the Seven Fat Years of Egypt. BUT a Pharaoh has arisen in this land, who knew not our Joseph, and his name is Agricultural Overproduction.

The needy years of the World War called area souiiesJern awav the grass and ft m'Ox By Dr. Frank Thone GRAT -YELLOW dust, borne on a dry scornful wind, fogged out the sun over eastern seaboard citie a few! weeks ago. People looked and wondered. Housewives were annoyed: more cleaning to dbi Airplanes had to stay grounded Port navigation was doubtful for a day or two. Then the cleared, and business went briskly forward again.

But people remembered. For a long time they will remember. They will tell their children, their grandchildren, of the Great Dust Storm of '34. They have this portentous thing to teH about as long as they live. But only on one condition.

That is, that they now take steps to keep others like it from coming again from coming again so often, and so calamitously, that there will be no thrill in the telling, because suchi storms shall have become a burdensome commonplace. An impoverishing commonplace, too. For when the peeved housewife re-vacuumed her rugs and dusted her furniture, after the sifting dust had passed on, she was throwing bread out of the house. Not this year's bread. Next year's.

Bread that might have grown as wheat on a farm in Kansas or western Iowa, but now can never be harvested or milled or baked. Lost bread. For that! great dust storm, the first of its kind, that ever blew so far as the eastern seaboard, was made of the best topsail of the mid-western grainlands. It had the mineral elements in it. that are needed by plants, to be added to water and air and sunlight to make food.

Lost from the farms, it can never be replaced or, at any rate, not in humanly calculable time. Dust storms like that have been fairly frequent things, of late years, but only in the midwest- They start in Colorado or Nebraska, choke lungs and sting eyes in Iowa and Illinois; not until this year have they, ever readied the east TN ancient times such an unfamiliar event would have been regarded as a portent and a sign of warning of disaster to follow, as was the Darkness over Egypt in the rime of Moses itself not improbably just such a dust storm. Our dust storm was a portent and a sign of warning, needing no supernatural sanction to make its lesson clear for the eyes and the minds of people who are thinking as many are thinking hard today. It was a sign of warning that the farm problem of the midwest' is a national problem, not a regional one. It was a warning that the soil there, and elsewhere in our country, too, is in danger of becoming a nomad soil, a gipsy soil, abiding nowhere, profiting nobody, turning from its age-old function of creating wealth to a new racketeering occupation of destroying property and impoverishing the people.

It was a warning that under our planless, systemless, anarchic mode of land use we are about to make a reality out of a myth. We Not snoTDjust good farm land gone bad. farmstead, it ruins the buildings climate and brought the region to agricultural suicide. China can tell us about that kind of thing, and so can Not very long ago, a scholarly Chinese was talking to a well-known, widely traveled American newspaperman. A is a hideous gash of raw clay.

A striding an advanced stage. drought was over China, with famine certain to follow, 'and a dust storm was raging outside as he spoke. Said the Chinese: "These droughts, dust-storms and famines are just what you Americans are in for unless you wake up in time. I can understand them in China because the damage was done centuries, even thousands of years ago before people knew what deforestation and bad farming could do to a nation. But I cannot understand a country like the United States allowing such a thing to happen China, he added, ought to be the "horrible example" in this respect to all the rest of the world.

China is not asleep any longer, either. China is out to salvage the fertile lands she has left, and even to redeem the desert, if "domestic fury and fierce civil strife." and the ambitions of imperialistic foreign powers, only let her. A dozen years ago a quiet young Chinese was studying in the botany department of the University of Chicago. "When I finish here, I go to Yale, study forestry." he explained to an American fellow-student. The American looked his surprise: he had always understood there were no forests in China.

"Oh, yes," the Chinese continued, with a quick smile: fyour foresters have as their task to conserve the forests. It will be my job in China to make some forests!" America might do well to follow the good example of this modern Chinese scholar. Service.) Copyright. 1934. by EveryWeek Magazine and Science illlHlllllllllllllDlllllllllilllllllllli..

Get access to Newspapers.com

- The largest online newspaper archive

- 300+ newspapers from the 1700's - 2000's

- Millions of additional pages added every month

About The Republic Archive

- Pages Available:

- 891,460

- Years Available:

- 1877-2024