The Sydney Morning Herald from Sydney, New South Wales, Australia • Page 15

- Publication:

- The Sydney Morning Heraldi

- Location:

- Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

- Issue Date:

- Page:

- 15

Extracted Article Text (OCR)

jjlmfj Pontine rralb 15 smh.com.au Wednesday, October 24, 2001 TO CHINA WITH LOVE The long wait for Xiao Ling n- Nobo dy if here Ministry of Civil Affairs in 1 996, which then created the Chinese Centre for AdoptioaAffairs. Karleen Gribble, who is planning to adopt a child from China, has been dealing with the NSW Department of Community Services for almost six years and has found the process testing. "It's a very bureaucratic process and the department isn't easy to work with. They make it unnecessarily difficult," says Gribble, who will leave with her partner for China in five weeks. They hope to bring home Xiao Ling, a three-year-old girl and orphan from the city of Xuzhou.

"You are treated as if you are a child. DOCS wish to protect you and make choices for you, which I guess isn't what most people want. DOCS are not very user-friendly. You might expect you would get a lot of help and support but, in fact, it seems a lot of people need help to survive the department." While Gribble believes that the interests of the child should be paramount, she also says that the department should be more considerate of prospective adoptive parents' needs. But a spokesman from DOCS said: "In NSW the adoption system is designed on the premise that adoption is a service to a child not the parents." He also said NSW had about 600 people wanting to adopt children, yet only 75 children a year were allocated from other countries.

Jessica Halloran Intercountry adoption now a more common way for parents to adopt rather than through local agencies can be a long and trying process. China is the latest country to sign an agreement to allow Australians to adopt its children. The Australia and China Adoption Agreement came into effect on December 28, 1 999, after six years of complex negotiations, conducted for Australia by the Victorian Department of Human Services with help from the Australian embassy in Beijing. Since then, more than 100 children have been placed with Australian families. "Australia has previously and still has formal adoption relations with Korea, Thailand, the Philippines and India," says Helen Brain, manager of adoption for the Victorian Department of Human Services.

Australia has adoption agreements with 13 other countries. Brain says negotiations with China were necessarily time-consuming. "The Chinese Government's Centre for Adoption required adoption orders to be automatically recognised by the receiving countries. This required amendments to Australia's Family Law Act, and regulations had to be amended through Parliament and by the Commonwealth Attorney-General." It was further complicated by internal Chinese bureaucratic changes: the initial talks were conducted by China's Ministry for Justice, which then changed to the tf tt I0m -Z ft i ySSL. if 1 HE mirror tells Ngita Bowers that she looks Indian.

But when she dreams, she is "very white," right down to the arms and aftffosfi museum numm iMhM fSSW the clothes and cooking the food. But Bowers, a media buyer for a North Sydney advertising agency, wants little to do with the culture of the Indian -sub-continent, including Bangladesh. "I have done the trips to India and I feel no connection with it whatsoever. I should have been born in Europe and my mother should have been born in India," she said. The book in which the "first wave" of adoptees from 18 countries through Africa, Asia and Latin America lay bare the emotional threads of their unusual lives shows that such outright rejection of birth culture is unusual.

Indeed, the common cry to new and would-be parents as is: "Don't just adopt the child, adopt their culture." Bowers cannot say whether growing up with adopted siblings from Bangladesh in an Indian-focused household made her strong enough to shun her birth heritage. Other contributors to the book appear to have suffered terribly from cultural isolation, marooned in a sea of whites confident in their identity. Often such adoptees learnt to hate the mirror and family photos because they saw how different they were, said Lynelle Beveridge, founder-director of the Inter-Country Adoptee Support Network, which now has 80 members. These were the types of revelations editors Sarah Armstrong and Petrina Slaytor sought when they edited the book for the Benevolent Society's Post Adoption Resource Centre (PARC), which saw an upsurge in the past few years of clients grappling with the legacy of cross-cultural adoptions. Incomplete figures show that at least 4,700 children from more than 18 other countries have been adopted by Australians since the 1970s.

PARC workers, who have talked to more than 20,000 people about adoption issues over the past decade, found new and complex issues emerging in counselling sessions with transracial adoptees but there were few resources to assist. "This is a very public adoption. Total strangers can see you are not the appearance by scrubbing, bleaching, tearing their brown skin from the imagined white self that existed below the On a happier note: "There was a collective sense of fond embarrassment at the efforts their families had made the attempts at creating the food of their culture the Colombian carvings and Chinese ornaments -coupled with a generous appreciation of the good intentions that these efforts had represented. There was a general agreement, however, that one's original culture can only be learnt from somebody of that culture." Bronwyn Taverne, president of the birthchild of your parents," said Armstrong. "It's a struggle to establish identity among white birth families, but put on top of that the question of racial identity and having no-one from that culture to teach you to have pride in it." Eleven of the 27 adoptees whose stories are told in the book described their adoptions as difficult.

Some were abused, but even many of those whose family life was smooth had to deal with confusing feelings of being white people trapped in different-looking bodies or of being required to show gratitude for having been Several, said the editors, "described a wish or a real attempt to change their hands she sees before her. "It just goes to show how Westernised I am, how integrated into the supposedly white culture," said Bowers, who in 1976 became the first child to be adopted from Bangladesh by Australians. She was found on the streets of Dacca, starving and beaten up so badly that she was taken to Mother Teresa's home for the dying. She still puzzles over "inexplicable scars" on her body. She does not know who her birth parents were.

Her "birthday" is March 28, the day she was handed to a nutritional centre which brought her back to health. Though she is officially 27 her age was estimated on her weight when she arrived in Australia -Bowers believes she is older. At school, she developed physically ahead of her classmates. Bowers has "a very distinct memory" from babyhood of someone trying to drown her by holding her head underwater. "I can still taste the dirty water in my throat that I'm choking on.

It is my mother who is holding me under the water and there is no way anyone will ever budge me on that point," she said in a chapter she wrote for a book to be launched tomorrow, The Colour of Difference -Journeys in Transracial Adoption. Among the 27 personal stories in tfie book, this wisp of memory or imagination makes hers one of the most shocking. But of all the contributors, who include 18 adopted from other countries, she is also one of the most positive about such adoptions. "Transracial adoption is a better option than same-race adoption because it's more honest. It forces the child and the parents to be honest as well," she said this week.

Bowers grew up in Sydney surrounded by things Indian. Her mother, an antique dealer, is passionate about that country, decorating their home with its arts and crafts, wearing disapproved, he has, like Beveridge, found multicultural Sydney a relief. His childhood, he said, was Visiting America, where he was accepted among black communities, he finally felt a sense of belonging. He now has African friends. "When I sit in a Vietnamese restaurant, I feel like a ghost because everyone else looks Vietnamese and I don't.

It's been the whole issue of my life, claiming an He changed his surname last year to Obataiye, a Nigerian word he found on the Internet meaning "king of a "I've had a lot of confidence struggles through my life. I thought I would give myself a name which is really powerful." Obataiye, just one exam short of becoming a qualified fitness instructor, rates his chances of finding his parents "zero to minus 1 He used to be angry at his birth mother, but believes that by leaving him outside a Saigon church, she was doing her best. He was raised for his first two years by a Canadian priest. On a visit to Vietnam two years ago he was told by an old woman that it didn't matter if he knew his parents: "You just look in the mirror and see them." That is what he does. The Colour of Difference Journeys in Transracial Adoption, Federation Press, $29.95.

and others give talks to adopting parents. There are plans to run camps at which older adoptees can mentor teenagers during a time when their sense of identity is most vulnerable. The aim, she said, is not to blame, but to promote honesty and to let others learn from past mistakes. A problem server with the IT company IBM GSA, Beveridge, 2S, was adopted froiiiVietnsiii into a Victorian country family which she said mistakenly believed "love could conquer "I did feel very alone and very isolated, even in my own family." She feels her parents floundered without help. As a war baby, she had a "starvation mentality" and bewildered them by hoarding food.

She was told her birth mother was probably a prostitute which hurt. On a voyage of discovery to Vietnam, she found that many poor women had to give their children up to save them. Now she tells parents to be very careful of what they say in front of their adopted children. Damian Obataiye, war child of a Vietnamese mother and African-American father, was adopted into a white family who lived in Wagga and Broken Hill. After a childhood of teasing and taunts, with friends whose parents would not let him play at their houses and girlfriends whose families Australian Society for Inter-Country Aid to Children, representing about 300 adoptive parents, said that adopting three children from Korea and Thailand was for her and husband Philip "the best thing we have ever done in our They have relished becoming friends with people from their children's cultures.

They have taken the. children back to their birth countries, made firm friends with other families who have children from the same countries in their home shire of Sutherland, and when the children were young, attended Korean festivals. Taverne is aware of the identity questions raised by looking in a mirror. "It does help that there are three of them because they are very close and have each other to look at. It's an issue I'm aware of.

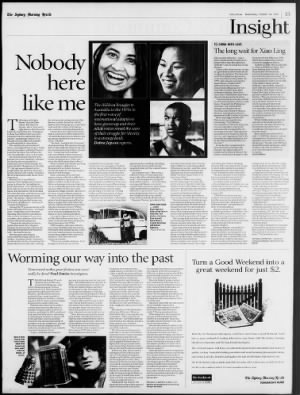

It's important for them to have contact with people of their own race so they can develop a positive self-image." Her teenage girls can share make-up and clothes tips with other Thais and Koreans because what suits their mother will not necessarily suit them. Beveridge said some parents were afraid that the new voice adult adoptees have found would be used to blame the white families who took in children of other races. The adoptees' organisation has its Web site (www.geocities.comicasnl) where members tell their stories. Beveridge Home sweet home Lynelle Beveridge as a child on the farm in Australia. Top photos, clockwise from top left, Ngita Bowers, Lynelle Beveridge and Damian Obataiye.

Photos: Peter Rae ieLi-'' -CC' Worming our way into the past Turn a Good Weekend into a great weekend for just $2. Time travel makes great fiction, but can it really Jbe done? Paul Davies investigates. MB 11 IW necessary to travel at near the speed of light 300,000 kilometres a second. At 99 per cent of this speed, a rocket trip to the star Alpha Centauri and back would seem to take 15 months, but you would return home to find that nearly nine years had elapsed on Earth. In effect, you would have leapt several years into Earth's future.

Gravity offers another way to slow time. On the Earth's surface, clocks tick a little slower than on the moon, for example. Near a neutron star or black hole, gravity is so intense that time is slowed to a crawl relative to us. These facts are accepted by almost all scientists. Travelling forwards in time has been demonstrated convincingly in many experiments.

However, the possibility of travelling backwards in time is far more controversial. The first hint that it might be possible came in 1932 when a little-known physicist named van THOUGH cult British TV sci-fi character Doctor Who was pensioned off long ago, time travel remains a popular science fiction motif. H. G. Wells blazed the trail with his 1895 story The Time Machine, and the theme has been revisited often most recently in Michael Crichton's Timeline, a rollicking yarn of 2 1 st-century archaeologists projected into medieval Europe.

Physicists have known for nearly a century that travel into the future is possible. Einstein's special theory of relativity, published in 1905, predicted that time should be elastic, stretching or shrinking as an observer moves. Fry to Rio and back, and you will find yourself a few nanoseconds adrift of youfstay-at-home neighbours. Though this tiny temporal slippage hardly makes for an adventure, it can easily be measured by atomic clocks. To get a really big time warp it is For example, laser beams can produce tiny regions of the electromagnetic field that, in theory at least, should be gravitationally repulsive.

So a worm-hole is not physically impossible. Once the Caltech group realised this, it dawned on them that such a structure could be adapted to make a time machine that would allow an astronaut to leap almost instantaneously into both the past and future. Go through the wormhole one way, and you reach the future. Go through the other way and you come out in the past. Making a traversible wormhole presents formidable engineering challenges, but suppose it could be done, and time travel became a reality? Thorny paradoxes loom.

What happens to the temponaut who goes back and murders his mother as a young girl? Does that mean he was never born? If so, who murdered the mother? Because the present is linked to the past, you cannot change the past without unleashing causal mayhem. Since the purpose of science is to give a rational account of reality, any theory that permits paradoxical consequences is suspect. Does this mean Einstein's theory of relativity is wrong, or that wormholes could never form? Or is physical reality a more subtle nature than we suppose? Although theoretical investigations of time travel have become something of a cottage industry among physicists, there is no consensus on how to deal with the ensuing paradoxes. But one thing is agreed. Borrowing the money to build a time machine should be no problem.

Once the device is made, you could visit the year 2 100, check out the stock prices, and then pop back and make the right investments to repay the loan. The Guardian Paul Davies's book Hew to Build a Tims MachinemW be published in Australia by Viking in December. Stockhum investigated what might happen to an observer who orbits a rapidly spinning cylinder. Using Einstein's theory of relativity, generalised to include the effects of gravity, van Stockhum showed it was possible to travel in a closed loop in space and return to your starting point before you left. Most scientists regarded van Stockhum's work, and several subsequent scenarios, as mathematical curiosities rather than realistic possibilities.

That changed in the late 1980s with the discovery that wormholes in space might provide portals to the past. Wormholes are like black holes, with a key difference. Whereas black holes offer a one-way journey to nowhere fall in and you can never get out wormholes have an exit as well as an entrance. If such a thing existed, you could fall through it and come out in a distant part of the universe The idea was made famous by Jodie Foster, the star of the Robert Zemeckis movie Contact, based on the eponymous novel by Carl Sagan. Foster gets dropped into a sort of gigantic kitchen mixer in Japan and emerges minutes later near the star Vega.

It looks terrific, but can the idea be taken seriously? To find out, Kip Thorne and his colleagues at the California Institute of Technology investigated what it would take for such a short cut through space to exist. They discovered that if you tried to make a wormhole out of any normal form of matter, it would collapse under its gravity and turn into a black hole. For a wormhole to remain stable for long enough for Foster to get through, it would have to be made of exotic material that would create an antigravity force. Problematic that may be, but physicists know of peculiar states of matter that generate antigravity. Back in time Doctor Who in his Tardis made time travel look easy, apart from the Daleks, of course.

With the $2 Weekend subscription, you'll have more than a Good Weekend. You'll have a great weekend of reading delivered to your home with The Sydney Morning Herald each Saturday and The Sun Herald on Sunday. The weekend papers will keep you informed, inspired and entertained with hours of quality reading. Australia's leading journalists and award-winning photographers bring you in-depth articles, features and quality sections on the topics that interest you. The $2 Weekend is only available until 30th November 2001.

Call us now on 1800 25 25 25. The offer is only available in NSW ACT here normal home delivery exists. 'sr lit i-r. I lb WWW 3Thf SjiMfti JRornuuj ralb roMOftKOWS paper rfiG cf Sunday.

Get access to Newspapers.com

- The largest online newspaper archive

- 300+ newspapers from the 1700's - 2000's

- Millions of additional pages added every month

Publisher Extra® Newspapers

- Exclusive licensed content from premium publishers like the The Sydney Morning Herald

- Archives through last month

- Continually updated

About The Sydney Morning Herald Archive

- Pages Available:

- 2,319,638

- Years Available:

- 1831-2002