The Courier-Journal from Louisville, Kentucky • Page 131

- Publication:

- The Courier-Journali

- Location:

- Louisville, Kentucky

- Issue Date:

- Page:

- 131

Extracted Article Text (OCR)

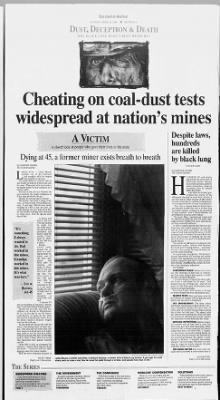

fje ourur-3onntal SUNDAY, APRIL 19, 1998 SECTION UUST, liECEPTION EAT WHY BLACK LUNG HASN'T BEEN WIPED Oil 8 III I II Ml IIIMlHllni I iiiMII Mllllllllll 1 A I'. -A ii. 5 f- i T. A i- 1 if: "i tt -J- ii 4 culxLiistt teste heaflMg oe coal. i widespread at mmes A Victim A closer look at people who gave their lives to the mine Dying at 45, a former miner exists breath to breath Despite laws, hundreds are killed by black lung First of five parts By GARDINER HARRIS The Courier-Journal UNDREDS OF coal miners nationwide die each year of black-lung disease because many mine operators, aided by miners themselves, cheat on air-quality tests to conceal lethal dust levels.

And while the federal government has known of the By GARDINER HARRIS The CourieisJournal LOGAN, W.Va. Leslie Blevins stumbles out of the bathroom and struggles with the oxygen tube hanging on the door. His hands shake so violently that he has trouble putting the forked tube into his nose. Wide-eyed with desperation, he finally inserts it, then collapses on a nearby couch. His hair is wet, his face flushed, his eyes watering.

He coughs and gasps as if he's been punched in the gut. Blevins, 45, has just taken a shower. The former coal miner is dying of silicosis, a virulent form of black-lung disease. A year ago, Blevins was slowly walking six miles a day. By July, he could manage just two miles.

Last fall, he had trouble walking from bedroom to living room. Now he spends most days in bed. A doctor told him in 1995 that if he quit mining I c- A I foYtjftlflWW 4.: I fc. ft H- -n 11 KtoMiMKM'mMlk 4S i i 4 he might live two more years. He outlived that prediction and hasn't asked for another: "I don't want to know.

I'll just take it as it comes." Blevins worked underground for 21 years as a mining-machine operator, one of the most dangerous and dusty jobs in America. His lungs are black, but it's not coal dust that's killing him. For three months in late 1993 and early 1994, he cut through sandstone to get to a coal seam. Sandstone's silica-laden dust is much more "It's something I always wanted to do. Dad worked in the mines, Grandpa worked in the mines.

It's what was here," Leslte Blevins, age 45 -i 'iff widespread cheating for more than 20 years, it has done little to stop it because of other priorities and a reluctance to confront coal operators, an investigation by The Courier-Journal shows. "Yes, even a cursory look (at federal dust-test records) would lead one to believe that inaccurate samples continue to be submitted in large numbers," said J. Davitt McAteer, the government's top mine-safety official. The result: Many underground miners toil in coal dust so thick that over the years their lungs become choked with scars and mucus, and they eventually suffocate. In 1969, Congress placed strict limits on airborne dust and ordered operators to take periodic air tests inside coal mines.

The law has reduced black lung among the nation's 53,000 underground coal miners by more than two-thirds. But because of cheating, the law has fallen far short of its goal of virtually eliminating the disease. The number of sick miners is unknown, but government studies indicate that between 1,600 and 3,600 working miners and many retirees have one of the lung disorders collectively called black lung. In a year-long investigation, The Courier-Journal interviewed 255 working and retired miners in the Appalachian coal fields and analyzed by comptuer more than 7 million government records. Unearthed was a mountain of evidence that cheating is widespread.

The findings: WIDESPREAD FRAUD: Nearly every miner said that cheating on dust tests is common, and that many miners help operators falsify the tests to protect theirjobs. "I've never known of one to be taken right, and I was a coal miner for 23 years," said Ronald Cole, 52, of Virgie, who left the mines in 1994. Like many of the miners interviewed, Cole has black lung. Two dozen former mine owners or managers acknowledged that they had falsified tests. TAINTED TESTS: Most coal mines send the government air samples with so little dust that experts say they must be fraudulent.

LAX ENFORCEMENT: The Mine Safety and Health Administration ignored these obviously fraudulent samples for more than 20 years, until The Courier-Journal began asking about them late last year. The agency also paid little attention during the 1970s and 1980s to government auditors and outside experts who repeatedly warned about dust-test fraud. BOTCHED INSPECTIONS: Agency inspectors oversee tests at least once a year, but these tests also have been inaccurate. Many inspectors fail to closely supervise the miners taking these tests, and since 1992, 11 inspectors have been convicted of taking bribes. In recent years, the government has improved its test monitoring because the agency is now headed by McAteer, a longtime mine-safety advocate.

Yet even today tests that are overseen by inspectors rarely measure the dust levels that miners actually breathe. THE UNION FACTOR: Dust tests tend to be taken more accurately at union mines than at See CHEATING Page 4, col. 2 this section J- i damaging to lungs than coal dust. "I knowed I'd pay for breathing all that dust," Blevins said. "I just didn't think it'd be this quick." Blevins and his wife, who have two children, are driving to Morgantown, W.

on this day to see his doctor. Linda Blevins, 41, packs the car. Then she and her husband, who heaves from the effort, wrestle a 40-pound oxygen tank into the back seat. As they drive off, the car fills with the sweet, intoxicating smell of fresh oxygen. They pass the coal trains that coat their house with black dust each night, then settle in for the four-hour drive.

Without noticing, they pass an exit that leads to Hawk's Nest, where the world first discovered how quickly silicosis can kill. From 1930 to 1933, an estimated 764 laborers mostly black migrants from the South contracted silicosis while digging a tunnel for Union Carbide. Still the worst industrial disaster in See HE TAKES Page 5, col. 1 this section I BY STEWART BOWMAN, THE COURIER-JOURNAL Leslie Blevins, a former coal miner, is dying of silicosis, a virulent form of black-lung disease. A year ago, he could slowly walk six miles a day.

Now he views the world through a window, and spends most days in bed. The Series WORKERS' COMPENSATION Kentucky Gov. Paul Patton and the legislature ignored most medical research when they overhauled the workers' compensation program in 1996, denying benefits to most black-lung victims. SATURDAY SOLUTIONS While the federal mine-safety agency wants its inspectors to eventually supervise all dust tests, lawsuits and criminal prosecutions against cheating coal operators may be more effective. NEXT SUNDAY THE COMPANIES With times tough in the coal mining industry, unionized operators who are safety-conscious, are getting squeezed by non-union companies that often cheat.

TUESDAY THE GOVERNMENT Despite repeated warnings, federal officials for decades ignored the widespread cheating. Many mine inspectors also have helped dust-test fraud thrive. TOMORROW WIDESPREAD CHEATING Coal miners are dying of black-lung disease because many mine operators routinely falsify government-mandated tests intended to keep coal-dust levels in check. TODAY.

Get access to Newspapers.com

- The largest online newspaper archive

- 300+ newspapers from the 1700's - 2000's

- Millions of additional pages added every month

Publisher Extra® Newspapers

- Exclusive licensed content from premium publishers like the The Courier-Journal

- Archives through last month

- Continually updated

About The Courier-Journal Archive

- Pages Available:

- 3,667,618

- Years Available:

- 1830-2024